By Zoe Reiter and Max Heywood, TI’s Americas department. Lea este artículo en español aquí

By Zoe Reiter and Max Heywood, TI’s Americas department. Lea este artículo en español aquí

We were recently in Peru with three of our national chapters to discuss the findings of a TI pilot project Economic Equality in Latin America that aims to make Conditional Cash Transfer programmes (CCTs) in Bolivia, Guatemala, and Peru more transparent and accountable. CCT programmes are one of the most important vehicles for raising the living standards of the poor and breaking inter-generational poverty in almost every country in Latin America (and, increasingly, around the world).

CCTs give cash directly to tens of millions of the poorest households that in turn meet “conditions” designed to help ensure that families are able to pursue sustainable livelihood strategies over the long term, such as sending the children to school or getting regular health checkups.

The premise behind TI’s project is that in order for these programmes to be most effective in raising the living standards of a country’s poorest population, they must have transparency and accountability mechanisms that ensure the “right benefits get to the right people at the right time.”

The key is to make sure CCTs reach those in greatest need and that the programs, at any level, do not fall prey to corruption or abuse of power. We want to help avoid cases where poor households that should qualify for benefits are unfairly excluded from receiving them because they do not respond to local or national political patronage. The project looks at all the phases of the CCT programme, from planning to delivery and evaluation, in order to identify where risks are most likely.

TI chapters then “drill down” on these identified areas of risk. They work with local communities to see, for example, to what extent families are aware of and effectively able to exercise their rights and responsibilities under the programme.

It is crucial to reach poor families that do not benefit from the programme yet, even if they have a right to.

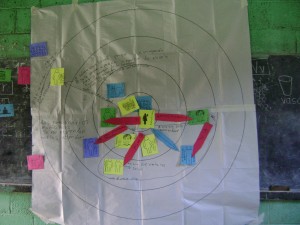

Local community leaders and beneficiaries in Guatemala map out key local actors involved in the CCT programme

Local-level participatory research identifies opportunities and practices that work towards incorporating the voices of the most vulnerable households into the programmes. A part of this process includes facilitating communities to highlight which actors and institutions, such as mayors or local politicians, are most responsive to their concerns about the programmes.

Sometimes the way a local community would deal with an issue does not always mesh with the formal structure of the programme. The chart below shows who people turn to to get into the programme or resolve problems: i.e. local politicians and officials.

This chart shows the involvement of local actors such as municipal authorities in the CCT programme. For example, the villagers say that a citizen’s group –the Community Development Council - helps them access the programme and make complaints.

In this way TI takes its time-tested approaches of expert diagnosis and multi-stakeholder engagement, and adds an increased focus on empowering local communities to monitor the programmes and exercise their rights. After all, the people who are supposed to benefit from these programmes are best placed to monitor delivery and identify when it is not working.

In August 2011 TI will produce a Guide to Civil Society Monitoring of CCT programmes, based on experiences of the pilot project and also highlighting other experiences in the region. More information to follow shortly!

- TI chapters go to local, often far-flung, communities…

- …empowering them to improve the CCT programme.

- Participatory workshop with programme beneficiaries

Connect with us on Facebook

Connect with us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter

Follow us on Twitter