With the revision of anti-corruption laws and the selection of new leaders of the Anti-Corruption Commission (KPK), the second half of 2011 will be a decisive time for anti-corruption activist in Indonesia, Ilham B. Saenong, Manager of Anti-Corruption Information Center, TI Indonesia, reports.

Only a few years after its establishment, Indonesia’s Anti-Corruption body the KPK has prosecuted and sent to jail for corruption over a hundred high-ranking officials. It has won ALL its cases in the corruption court, with all appealed verdicts upheld by the Supreme Court.

In addition, the KPK has conducted extensive corruption prevention activities and recovered substantial state assets. It has helped to make corruption a more high-risk and low-reward activity than at any previous period in the country’s history.

Yet this year the house of representatives plans to revise the current Anti-Graft Act and the KPK Act. The Government says it prepared the Anti-Graft Act to comply with UNCAC.

However, the draft tends to reduce the legal penalties for corruption and allowing graft convicts to avoid prison. One amendment stipulates a minimum sentence of one year imprisonment for those convicted of graft, whereas today a corrupt official could get up to four years imprisonment.

After strong resistance from civil society, the provisional bill was recently sent back to the Ministry, which stopped the draft from entering the House. Yet there is no guarantee the bill will not be passed later this year. This was a positive change from previous “high-octane” proposals that had been passed quickly without (enough) public consultation.

Meanwhile, the KPK provision bill, as an initiative of Parliament, is also set up to become top priority in legislation this year. Even tough there is the public has yet to see a draft, the initiative has been much criticized as unnecessary and a move to strip the KPK of its authority.

“The proposed bill contradicts the nation’s commitment to tackling corruption,” said the Chief of the KPK himself, Busyro Muqoddas, who claimed his office was never invited to discussions about the bill. “There is no urgent need to revise KPK Act since the existing law is more than enough.”

The fact that the bills are top legislative priorities raise suspicion, since they came up suddenly, without any public polling or consultation with the KPK itself. To make things worse, there are members of the House who are currently being investigated by the KPK.

Stop amendments

Anti-corruption activists generally shared opinion that the two provision endanger the existence of KPK and corruption eradication. They fear they will strip KPK’s authority, weaken punishments, nurture culture of corruption, threaten the spirit of whistle-blowing, deteriorate confiscation of stolen assets and even free corruptors.

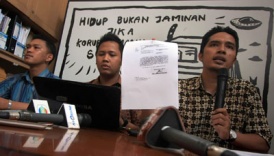

Anti-corruption activists urged government to stop the amendment of anti-corruption law

“These proposals are the real threat to the fight against corruption in our country,” said Teten Masduki, secretary general TI Indonesia. “It could become a deadly blow to the KPK, considering that majority of the existing Parliament members are against anti-corruption movement.”

TI Indonesia and other anti-corruption organizations held several press conferences in April calling on the Indonesian government and parliament to preserve the independence of the KPK.

The KPK has already faced threats to its independence. For, example, in September 2009, two KPK commissioners were arrested and later sent to court on the basis of accusation that they blackmailed a businessman (Anggodo Widjojo) in a case of his brother. The accusation was later proved to be a frame-up involving some law enforcement officers. The social movement to fight against this accusation was later being known as the Cicak-Buaya campaign.

Indonesian Corruption Watch, a leading anti-corruption watchdog, observes that there are at least 13 judicial reviews on KPK acts, most of them intended to undermine its authority to conduct prosecutions and special investigation.

Last year the government and legislative agreed to decrease KPK budget for corruption prosecutions to only Rp 19,2 billion (US$2 million) in 2011 from Rp 26,3 billion in 2010 (US$3 million). Members of Parliament, who have been among the most vocal in calling for reducing the KPK’s power, have even resorted to the threat of budgetary cuts to pressure the KPK into prioritizing specific cases over others.

In the current political climate (the ongoing corruption investigation and prosecution of 26 politicians/legislative members and many highly suspected politico-corruption scandals), initiatives to amend the laws should be seen as a new strategy to undermine the fight against corruption in this country.

No wonder corruption in this country remains pervasive, putting Indonesia’s score below 3 (10 most clean, 0 most corrupt) in TI’s Corruption Perception Index over the years. Without abandoning of the proposed bills, the KPK and efforts to eradicate corruption will be under constant and serious threat.

Connect with us on Facebook

Connect with us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter

Follow us on Twitter