Eduardo Bohórquez and Deniz Devrim of Transparency International’s Mexican Chapter reflect on their country’s efforts to fight foreign bribery and new opportunities for its upcoming G20 presidency.

Eduardo Bohórquez and Deniz Devrim of Transparency International’s Mexican Chapter reflect on their country’s efforts to fight foreign bribery and new opportunities for its upcoming G20 presidency.

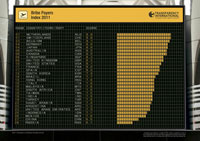

In the 2011 Bribe Payers Index (BPI), Mexico ranks on position 26 out of 28 countries with a score of 7.0 on a scale where 0 means Mexican companies always engage in bribery and 10 means they never engage in bribery when doing business abroad. These results come only shortly after the publication of the OECD report on the implementation of the anti-bribery convention in Mexico. Both – the BPI and the OECD report – reveal shortcomings in the enforcement of Mexico’s strategy to fight foreign bribery. Mexico’s presidency of the G20 in 2012 represents an important opportunity for the country to show consistency by aligning its domestic efforts with its new global responsibility.

Mexico has outlawed foreign bribery in the Federal Penal Code, but implementation still seems to be in its beginnings. In the framework of the OECD convention, Mexico reported two on-going foreign bribery cases that were opened in 2004 and 2005. While relevant in relative terms –given that these are the first two cases that Mexico has reported since the convention came into force in 1999–, this figure is still far from showing a consistent effort to reduce corruption and impunity in the relationship between the private and the public sector.

Mexico has outlawed foreign bribery in the Federal Penal Code, but implementation still seems to be in its beginnings. In the framework of the OECD convention, Mexico reported two on-going foreign bribery cases that were opened in 2004 and 2005. While relevant in relative terms –given that these are the first two cases that Mexico has reported since the convention came into force in 1999–, this figure is still far from showing a consistent effort to reduce corruption and impunity in the relationship between the private and the public sector.

Mexico is the 14th largest economy in the world and its annual budget for procurement at the federal level is reaching 10 billion dollars. But its efforts in fighting corruption in international transactions do not seem enough for the size of the problem. Compared to the number of cases that other countries have reported –Germany, 137 cases; United States, 227 cases; Hungary, 27 cases– Mexican efforts seem quite limited. The OECD report underlines that these two cases have progressed with a slow pace and expresses a broader concern over the low priority given to foreign bribery cases compared to other crimes. Prosecuting Mexicans alleged to be involved in corrupt practices outside the country remains a pending task for the future.

It is not only enforcement that should be high on Mexico’s anti-corruption agenda. The OECD Working Group is also concerned about aspects of the Federal Penal Code and suggests, for example, that the part on liability of legal persons should be amended, so that liability may be imposed without the prior identification or conviction of the relevant natural persons. Further, the report suggests that state-owned or state-controlled enterprises can be sanctioned for foreign bribery other than by dissolution of the legal person. The doubts expressed by the Working Group make clear that Mexico needs to prioritize the criminalization of corruption, as well as the enforcement of these laws.

The results of the 2011 BPI confirm that the world’s largest economies continue bribing when doing business abroad. Even though foreign bribery is outlawed in at least 24 of the 28 countries covered by the BPI, only few countries have proactive and coherent strategies to control their companies abroad.

The Mexican government has underlined that it is ready to maintain the central role that France has given to the fight against corruption. The promise to maintain the anti-corruption international agenda as a G-20 priority issue has to be followed by deeds. During its G20 presidency, Mexico should seek to undertake serious efforts in the implementation of the OECD convention. Its new role presents the challenge of leading global change while giving the necessary consistency to Mexico’s anti-corruption fight.

Connect with us on Facebook

Connect with us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter

Follow us on Twitter