In an opinion piece in the latest edition of New Europe Jana Mittermaier, Head of Transparency International Liaison Office to the EU, argues that if European leaders are serious about fighting corruption, they need to pay closer attention to the behaviour of their companies. The most recent results of the Bribe Payers Index (BPI) show that there is no room for complacency.

If the events of the Arab Spring have an enduring lesson it is this: countries ignore the corrosive effects of corruption at their peril. Watching the revolutions unfold from the safety of our living rooms, it would be easy to be complacent. Bribery and graft are things that happen “over there”, with rapacious and greedy elites leading the way. Our own complicity in this state of affairs is often ignored.

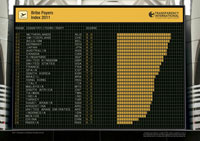

A new report by Transparency International shatters this comfortable illusion. It reveals that bribery and corruption are alive and well among the companies that are based in the EU – the all-important “supply-side” of corruption. The 2011 Bribe Payers Index ranks 28 countries according to the likelihood of companies from that country to offer bribes when doing business abroad. The ranking is compiled from a survey of approximately 3,000 senior business executives, and so taps into insider knowledge and perceptions. Scoring a perfect 10 in the ranking means that companies in that country are not perceived to engage in bribery at all. No country achieves this score. Even countries that pride themselves on their reputation for clean business – the Netherlands, Switzerland, Canada– are touched by perceptions of corruption.France and Spain are middle-ranking powers on this measure. Italy fares worse than Brazil- its peers in the business of bribery are considered to be Hong Kong and Malaysia.

A new report by Transparency International shatters this comfortable illusion. It reveals that bribery and corruption are alive and well among the companies that are based in the EU – the all-important “supply-side” of corruption. The 2011 Bribe Payers Index ranks 28 countries according to the likelihood of companies from that country to offer bribes when doing business abroad. The ranking is compiled from a survey of approximately 3,000 senior business executives, and so taps into insider knowledge and perceptions. Scoring a perfect 10 in the ranking means that companies in that country are not perceived to engage in bribery at all. No country achieves this score. Even countries that pride themselves on their reputation for clean business – the Netherlands, Switzerland, Canada– are touched by perceptions of corruption.France and Spain are middle-ranking powers on this measure. Italy fares worse than Brazil- its peers in the business of bribery are considered to be Hong Kong and Malaysia.

True, EU member states in general appear toward the top of the ranking, some distance above countries such asIndonesia, Mexico,Chinaand, in last place,Russia. This should be cold comfort, however. These countries, particularly China and Russia, have massively increased their levels of foreign direct investment (FDI) in recent years, making the most of commodity booms and large trade surpluses. The countries at the receiving end of Chinese and Russian investment feel the effects not just of the financial flows, but also of the associated business operations and activities. For example, Russian companies are increasingly present in the international oil and gas sector and China is investing heavily in infrastructure and mining, particularly in Africa. The growing importance of these emerging economies in international flows of trade and investment means that there will be increased pressure to compete in the bribery game.

The trend, moreover, is worryingly flat. Despite European countries signing up to a raft of international anti-corruption conventions at UN, OECD and EU level, there has been no improvement in the average performance of their companies since the last time this ranking was compiled in 2008. In many cases, governments have not lived to their high-level commitments and failed to put in place the necessary legislation or eliminate existing loopholes. For example, in too many countries “facilitation payments” are a legal grey area. These are payments made to officials to carry out or speed up actions that are part of their normal duties, for example approving visas or customs procedures. Even countries that have put in place gold-standard anti-bribery legislation, such as theUK, are sending out mixed messages by starving enforcement agencies of the necessary resources. The UK Serious Fraud Office will have its budget slashed by 25 % this year.

One of the surprising findings of the report is that corruption within the private sector – bribery of firms by other firms – is as common as bribery of public officials. Companies may engage in private-to-private bribery in order to secure business and facilitate hidden business cartels. Employees from large companies can exploit their influence and buying power by demanding bribes or kickbacks from potential suppliers. Bribery can also be disguised through offering clients gifts and corporate hospitality that are inappropriate in value. Its effects can be felt through the entire supply chain, increasing costs to firms, penalising smaller companies that cannot afford to compete on these terms and those firms with high integrity that refuse to do so.

One of the surprising findings of the report is that corruption within the private sector – bribery of firms by other firms – is as common as bribery of public officials. Companies may engage in private-to-private bribery in order to secure business and facilitate hidden business cartels. Employees from large companies can exploit their influence and buying power by demanding bribes or kickbacks from potential suppliers. Bribery can also be disguised through offering clients gifts and corporate hospitality that are inappropriate in value. Its effects can be felt through the entire supply chain, increasing costs to firms, penalising smaller companies that cannot afford to compete on these terms and those firms with high integrity that refuse to do so.

The EU recognised the distorting effect of this corruption on markets and competition as long ago as 2003, when the Framework Decision on Combating Corruption in the Private Sector was agreed. A comprehensive framework for prohibiting business-to-business bribery, it is binding on all EU Member States. However, a 2011 European Commission report found that its implementation had been “highly problematic” with only 9 out of 27 Member States putting in place key elements of the recommended legislation. This indicates the many obstacles on the path from political commitment to robust and effective laws.

European governments, through their pronouncements at EU and G20 level, have demonstrated an awareness of the devastating effects of corruption. The message from this report is clear: anti-corruption measures begin at home with a more ethical and transparent private sector.

Connect with us on Facebook

Connect with us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter

Follow us on Twitter