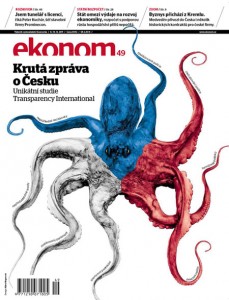

Recently TI Czech Republic launched a National Integrity System (NIS) assessment providing a ‘health check’ of the key governance institutions in the country, with special emphasis on how well resourced they are, how they fare on integrity, accountability and transparency, and whether they perform their role in the anti-corruption effort. It is part of a Europe-wide project assessing the integrity systems of 26 European countries.

The study was anticipated with interest by many in the Czech anti-corruption community, from NGO activists to responsible civil servants, since there are not many studies on corruption and anti-corruption policy in the country. Of course, the main expectations focused on the ’health’ of individual pillars of Czech society, from institutions like the judiciary and the police to actors like the media and civil society.

The study describes the nature of corruption in the Czech Republic. Despite faring quite poorly in the Corruption Perceptions Index in comparison to its European peers, the main Czech corruption problem is not one which most Czechs encounter on a daily basis. Instead it is a more hidden problem, thriving at the interface between public administration and business: namely, public procurement processes. This finding is important not only for the effective targeting of anti-corruption resources, but also for arguing against those who make frequent use of the term ‘corruption’ while neglecting the most prevalent forms of corruption in the country.

The results on the ’health‘ of individual institutions were perhaps not terribly surprising. The pillars with the highest scores were the Ombudsman and Supreme Auditing Office. These institutions appear as islands of integrity within the system, but the truth is that they have the least impact on society and ordinary citizens.

The lowest scoring pillar was the state prosecutor’s office followed by public administration and the police. These sectors lack independence from political parties and therefore show lower accountability and limited integrity, and ultimately do little to bolster the national anti-corruption effort. Meanwhile, these institutions command the highest level of resources, both economic and human. It should be noted that the worst scoring pillar – the state prosecutor’s office – is also the one which is currently undergoing the most profound changes in a positive direction. This indicates the ‘snap-shot’ nature of the study and the need for a follow-up study in the coming two to three years to monitor progress.

Another way of looking at the National Integrity System is to examine cross-cutting issues, like integrity and accountability across the entire system. Is it even possible to score well on issues like integrity or accountability when the Czech language does not even know such words? The initial difficulty in translating these terms foreshadowed troubles with gaining a clear understanding of social reality in different contexts.

When it comes to accountability, many issues were identified. In some areas like the police or public administration it was difficult to determine to whom the police should be accountable or which forms of accountability should be promoted. Legal regulations require a high level of personal accountability from individual police officers but the same is not true for the police as an institution. Meanwhile, the civil service lacks both individual and institutional accountability. One aim of the NIS report is to help open a discussion on how accountability should be conceived in the Czech Republic – a dialogue that may have profound implications on the new civil service legislation currently being drafted.

The same approach can be taken towards the concept of integrity. This concept is of course known and used in Czech society, but often as an empty rhetorical device without any impact on behaviour. Concrete integrity problems like conflict of interest and revolving door syndrome remain unaddressed by the current framework.

And finally, when it comes to transparency, the Czech Republic has quite comprehensive legislation on access to information, and the concept of transparency is frequently referenced. However, transparency in key areas – such as policy making, the legislative process and details of public spending – remains weak and inaccessible for most citizens.

There is much work to be done to strengthen the integrity system in the Czech Republic. This new report opens the door for dialogue with important stakeholders. In the years ahead, a follow-up study can help monitor the integrity of the system over time and tell us where progress has been made. In the mean time, TI Czech Republic will continue to fight corruption, basing its advocacy on the key problems revealed in the National Integrity System assessment.

Connect with us on Facebook

Connect with us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter

Follow us on Twitter