Transparency International’s National Contact in Vietnam, Towards Transparency, has just published a report on health. Our colleagues Stephanie Chow and Conrad Zellmann report.”

“Years ago, my 2-year-old son required surgery. I had a pre-existing relationship with a doctor at that hospital. But I was worried before the surgery when I had not given money to the surgeon. I did not know if my son would have enough care. After the surgery, I actively solicited the doctor to accept the money. I just felt a peace in mind from that moment.”

This statement was made by a patient interviewed in a new research study on informal payments in health services in Vietnam. Although it cannot fully capture the complex causes and consequences of informal payments, it provides a hint of the difficult choices faced by health care professionals and patients.

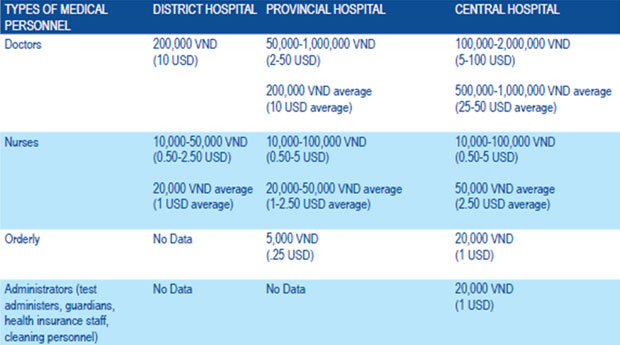

In Vietnam as in many other, including a number of European, countries informal payments in health are widespread. More than 30% of respondents in the latest edition of the Vietnam Provincial Governance and Public Administration Index (PAPI) reported experience with bribes in the health sector. Informal payments appear in various forms and are described using a number of different terms such as tien cam on (money to express thanks), phong bi (an envelope) or tien dut (bribe). Values of informal payments also vary greatly between lower and higher-level hospitals as well as between rural and urban health facilities, ranging from 50,000 VND (2.50 USD) to 5,000,000 VND (250 USD) with some reported exceptions valued up to several tens of millions Vietnam dong (several thousand US dollars).

Table 1. Ranges of Payment Amounts to Health Workers

Patients feel that such payments are necessary to access adequate treatment, and many health care professionals say they have no choice but to accept them to improve their meager salaries. It is sometimes argued that informal payments are made voluntarily, but testimonies such as this paint a different picture:

Patients feel that such payments are necessary to access adequate treatment, and many health care professionals say they have no choice but to accept them to improve their meager salaries. It is sometimes argued that informal payments are made voluntarily, but testimonies such as this paint a different picture:

“They have never directly asked for money. They do a very strong and painful injection to signal or prompt the payment. While if you have paid, the injection is gentle, and the medicine may be better….A number of health workers act badly if they don’t get an envelope payment from the patient.”

A young doctor profiled in the report tells the other side of the story. After years of study, she earns around 100 USD per month in Ho Chi Minh City, where the cost of living has been rising fast in recent years. She says that this is not enough even to cover her expenses without additional support from her family. She adds that she has not accepted any envelopes from patients, but feels that at some point financial pressure will push her to compromise her ethics. Another doctor interviewed in the study admits “Honestly, I have felt shameful to accept an envelope. But it [the acceptance] is compulsory. I am unable to feed myself if I do not receive it.”

Participants at a workshop we jointly organised on 6 June 2012, with our colleagues from the Research and Training Centre for Community Development (RTCCD) to discuss the report findings, highlighted numerous challenges faced by patients, policymakers and practitioners in Vietnam’s health care sector. Health managers and staff, representatives of civil society and government confirmed the key drivers of informal payments: Low salaries, over-crowding of public hospitals, pressure on hospitals to have financial autonomy as a result of the introduction of market-based management mechanisms in hospital management, inconsistent professional ethics of medical staff and managers as well as low levels of awareness of patients about the legitimacy of fees and about complaints mechanisms.

Participants at a workshop we jointly organised on 6 June 2012, with our colleagues from the Research and Training Centre for Community Development (RTCCD) to discuss the report findings, highlighted numerous challenges faced by patients, policymakers and practitioners in Vietnam’s health care sector. Health managers and staff, representatives of civil society and government confirmed the key drivers of informal payments: Low salaries, over-crowding of public hospitals, pressure on hospitals to have financial autonomy as a result of the introduction of market-based management mechanisms in hospital management, inconsistent professional ethics of medical staff and managers as well as low levels of awareness of patients about the legitimacy of fees and about complaints mechanisms.

Finding solutions to address informal payments in health services will not be without its challenges. Existing efforts such as the introduction of disciplinary actions for health workers who accept informal payments and open feedback mechanisms for patients to make complaints have been found to be nominal and not very effective. Discussions at the workshop revealed, that given many different causes of informal payments, solutions will need to be multifaceted, targeting both the technical structures within health systems and also wider social perceptions and behaviours.

Improving patient awareness of their rights and official fee rates, improving accessibility and effectiveness of complaints mechanism, introducing and enforcing codes of ethics, improving oversight by elected bodies and independent monitoring mechanisms, and piloting no-envelope programmes in a group of hospitals were just some examples of potential solutions raised.

The challenges in cleaning up Vietnam’s health services are no doubt huge, given the complexity of the problem. However, the passionate debate ignited at the workshop by senior health representatives, such as the heads of Vietnam’s Obstetric and Pediatric Associations, two departments where informal payments were found to be particularly pervasive, reveals an eagerness from within the health system to make a change. Combined with the finding from the latest Global Corruption Report (GCR) that 80% of Vietnamese can imagine getting involved in the fight against corruption (urban sample), this provides for hope that lasting solutions can be identified.

Connect with us on Facebook

Connect with us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter

Follow us on Twitter