A new index measures transparency in state-owned companies.

Ján Podhorský was appointed to lead Tepláreň Košice, hundred percent state-owned heating plant, in August 2010, soon after national elections. Podhorský was one of the hundreds of politically appointed managers who came to lead state companies after the electoral change. Nothing unusual in Slovakia, where two thirds of managerial positions change personnel within a year after elections, according to TI Slovakia analysis. Only 40 days into his job, Podhorský was replaced by another nominee thanks to a new political deal between two coalition parties. Departing manager ended up with a golden parachute of 90 thousand euros, or equivalent of a year worth of his salary.

The three Slovak state hospitals with the biggest procurement volumes receive on average only 1,1 bids per tender. The bidders who take part (or are allowed to take part) in procurement are almost certain to get the fat contract. Other Slovak state hospitals do not fare much better. Overall, two thirds of their total contracting is awarded to the only bidder entering the contest, indicating large corruption risks, according to Transparency International study released in mid-August.

Slovak media report frequently on cases of enormous benefits going to company managers, and overpriced purchases made by companies that provide poor services for their clients. Unlike ministries and other government institutions, the semi-commercial status of state companies exempts them from most of obligations of access to information laws. This makes public control rather weak. Yet Slovakia has around hundred fully state-owned companies with sales worth 12 billion euros annually.

That is why TI Slovakia launched its first ever Transparency ranking of state- and city-owned companies this summer. The rankings showed that Slovak companies scored poorly on most accounts.

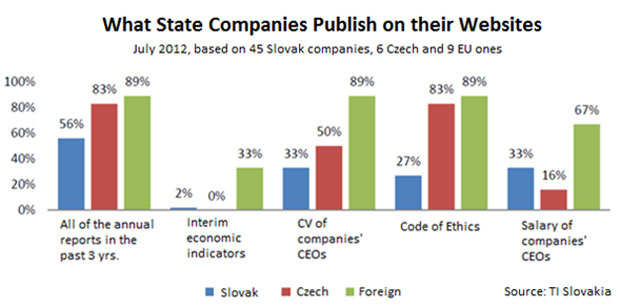

- Two thirds of them refused to disclose salaries and CVs of their CEOs.

- Half of the companies did not provide their contracts with their cleaning service providers.

- Three quarters do not have Codes of Ethics and almost 90% of the companies do not make specific performance targets public.

- Every sixth company does not even have a single annual report from the past three years published on its website.

- Moreover, Slovak companies did not fare well in comparison with similar state companies elsewhere in the EU (see chart below).

The state company rankings were the third of the series of assessment tools which TI Slovakia used in pushing transparency agenda in the public sector. In 2010, it measured openness of 100 largest cities in the country. A year later, it looked at all eight regional governments. Rankings focus on similar areas: budget transparency, public procurement, ethical standards, hiring and granting policies.

Media attention and competitive nature of researched institutions made many respond. The city of Svidník wants to make it to the top 20 Slovak municipalities in the next rankings, said the mayor of the city in eastern Slovakia. The leaders of the second largest city of Košice said they did not want to stay at the bottom of the rankings either, and were about to invest in an application facilitating easy access to all city contracts online.

Minister of the Economy Tomáš Malatinský responded to the company rankings the day they were published. He said he would act on the TI Slovakia’s recommendation to publish contracts of state company managers and regulate golden parachutes. DPMK, this year’s best-placed city-owned company paraded their good result in the separate press release.

Importantly, the websites visualizing the rankings do not include information only about how cities or companies fared, but also specific recommendations how to improve. Moreover, the websites enable easy comparison across indicators and provide all the data included in evaluation, thus making the scores verifiable and actionable. It is easy to see for any mayor or manager what needs to be changed and how much one can improve in the rankings as a consequence.

TI Slovakia hopes to repeat the rankings every two years. This would enable public to follow the track record of mayors or state managers. As for the future, we would like to set our sights on other areas suffering from little transparency, such as education or judiciary.

Connect with us on Facebook

Connect with us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter

Follow us on Twitter