Michael was the only person in the village who could speak English. He had learned it in Australia, and talked with a gentle upwards incline. As I spoke Michael interpreted into Suau (the local language), pausing intermittently for responses from the crowd. My audience was intimidatingly large – huddled rows of crossed legs and expectant faces, with many more watching on from porches or open windows.

This had not gone as expected. My colleagues at Transparency International Papua New Guinea and I had travelled to Leileiyafa to learn from the villagers about their experiences with the REDD+ process. “We don’t know anything about REDD+,” was their reaction. “We were hoping that you’d fill us in.”

This had not gone as expected. My colleagues at Transparency International Papua New Guinea and I had travelled to Leileiyafa to learn from the villagers about their experiences with the REDD+ process. “We don’t know anything about REDD+,” was their reaction. “We were hoping that you’d fill us in.”

Reducing Emissions through Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) is a UN-initiated scheme aimed at tackling climate change by enhancing the world’s forest cover. More trees equates to less carbon dioxide, thus less global warming. In the current economic climate, forests only really accrue value when they’re cut down. REDD+ is trying to reverse that logic. Developing countries with rich forest reserves are being offered compensation to ensure that their woodland stays rooted.

Explaining that is somewhat trickier when to a community who lives so deep within the forest that ‘emissions’ is an elusive concept.

Leileiyafa is located on one of five REDD+ pilot sites on the Papua New Guinea archipelago, in the southern province of Milne Bay. The roads that lead to it are so unruly that only a jeep can navigate them. The nearest secondary school is a two-hour walk away, meaning that most children forego a secondary education. Anyone needing medical treatment travels by dingy to the nearest hospital, one hour away. On the condition, that is, that the seas are calm. On stormy days you are safer staying put.

Leileiyafa is located on one of five REDD+ pilot sites on the Papua New Guinea archipelago, in the southern province of Milne Bay. The roads that lead to it are so unruly that only a jeep can navigate them. The nearest secondary school is a two-hour walk away, meaning that most children forego a secondary education. Anyone needing medical treatment travels by dingy to the nearest hospital, one hour away. On the condition, that is, that the seas are calm. On stormy days you are safer staying put.

In theory, REDD+ money could help change that, as a significant portion of the funds should be channelled into furthering local development. The fear in certain quarters, however, is that the funds will end up elsewhere.

These concerns are not unfounded – Papua New Guinea’s forests are a hive of corrupt activity. Politicians, companies and local leaders have conspired to sustain a thriving black market of illegal trade and tax avoidance, locking wealth inside elite circles while around 40 per cent of people live on less than US$1 per day.

Corruption has many guises. Often it is traceable to an act or an exchange – a bribe or a kickback, for instance. But it can also occur through a non-act – when people are strategically and wrongfully excluded from processes or profits to the direct advantage of others.

As my impromptu introduction to REDD+ reached its end, an elderly man with a baseball cap and cloudy grey eyes recounted the day that the Forestry Department had stopped by. Their promise – that the villagers would receive money for not cutting down trees. There was no talk of when that money would arrive, how much, or who would receive it. Nearly six months had since passed by in silence.

As my impromptu introduction to REDD+ reached its end, an elderly man with a baseball cap and cloudy grey eyes recounted the day that the Forestry Department had stopped by. Their promise – that the villagers would receive money for not cutting down trees. There was no talk of when that money would arrive, how much, or who would receive it. Nearly six months had since passed by in silence.

Local consultations – according to the principles of REDD+ – should not be one-way, irregular or elliptical conversations. Communities living on REDD+ sites should be partners in designing a system that suits their context and is fair and beneficial to all. The fact that the villagers of Leileiyafa – who own the land they live on – were unaware of what REDD+ is signals an inauspicious start to the scheme in that region. The risk is that REDD+ money will never find its way to them, or will amount to less than it should.

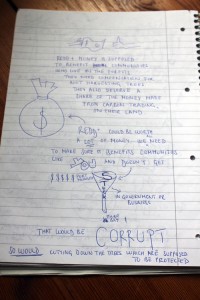

I left Leileiyafa with a small cache of hand-drawn illustrations. The REDD+ leaflets that we had brought with us were largely redundant, as much of the village’s population was illiterate, so I tried to communicate the fundamentals visually. These were the first in a long line of sketches that were to culminate in a campaign poster – aimed at piquing people’s interest in REDD+ opportunities and risks, and connecting them to local sources of advice. The poster presents alternative scenarios – what happens when REDD+ works, and what happens when corruption creeps in. This month our REDD+ team will roll out the campaign to REDD-affected communities in Indonesia, Papua New Guinea and Vietnam. We hope that it will go some way to plugging knowledge gaps like the one we encountered in Milne Bay.

Connect with us on Facebook

Connect with us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter

Follow us on Twitter