on articles from the forthcoming project

It Belongs to You: Public Information in the

Middle East and North Africa.

Behind the imposing edifice of the shiny Egyptian World Trade Centre on the corniche in Cairo lies the decrepit hospital of Boulaq Abu Ela. A rubbish heap surrounding the hospital’s ailing walls adds to this staggering contrast. This is the scene that confronted me when I first went there to find out why this hospital was in such a horrible condition.

Boulaq is an important neighbourhood in the geography and history of Cairo and the residents I met through my work with the Egyptian Initiative of Personal Rights had had enough and were fed up with decades of neglect and corruption. The hospital is located in one of the most lucrative stretches of the city and national and local authorities and businessmen have long earmarked it for investment.

For over a decade, the Health Ministry tried to sell the hospital. Then, in 2004, it struck a LE40million ($5.78 million) deal to renovate the hospital, starting with the demolition of the kidney dialysis annex. But the renovation never happened, the annex has not been rebuilt and vital medical equipment for patients is missing. Neither the hospital administration nor the ministry have said if or when the renovation process will be complete.

Boulaq is symptomatic of other hospitals in Egypt that suffer from a general lack of accountability and transparency in planning. Large disparities in equitable healthcare coverage persist. Here are some sobering facts:

- Only about 51 per cent of the population has health insurance.

- Annual public healthcare spending in 2012/13 stands at some LE27.4 billion (roughly US$4.5 billion), accounting for only five per cent of the total state budget.

- Nine per cent of all hospital beds across the country are in private hospitals, putting more pressure on the public health system.

- Around 200 hospitals and 3,800 medical units are said to be in inadequate condition to provide medical services.

- Nearly three out of four Egyptians think that there is corruption in medical and health services provision.

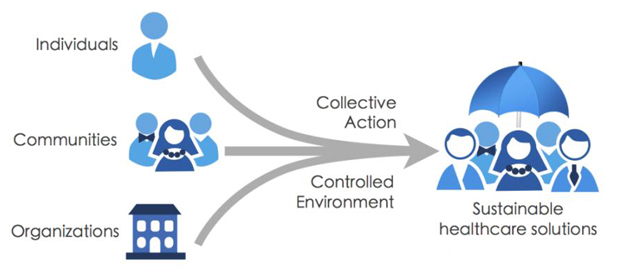

This is what I, along with my colleague Mohamed Abdel Raouf (also featured in the film), embarked upon to fix. We started Shamseya, an organisation that seeks to build the healthcare system from the ground up through extensive community participation using a micro-insurance model. We wanted to know why public funds were not going to the people who most needed to access healthcare. We wanted to remedy the lack of information from government officials about laws and decisions that would affect people’s health.

We are working with people in local communities such as in Hay El Gazzareen (Butchers’ Town) who put forward their own solutions to their daily problems in a transparent manner that bypasses state bureaucracy. We hope to continue our small revolution and empower people to demand information about their healthcare and make informed decisions that lead to transparency and improved services.

Connect with us on Facebook

Connect with us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter

Follow us on Twitter