The annual gathering of a majority of Asia Pacific countries at the tail end of the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) 2013 casts doubt on the prediction that the 21st century will be the Asian century.

Over the past decade many countries in the Asia Pacific region have achieved commendable economic and social growth. But have the governments in the region managed to secure the confidence of the people as public trustees for a sustainable development?

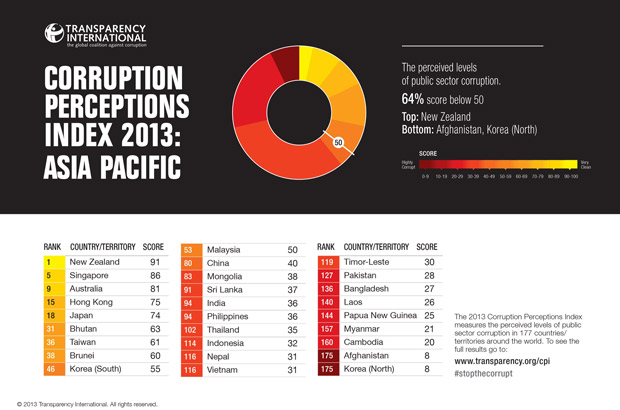

The results of Corruption Perception Index 2013 reveal a high level of public sector corruption. This indicates failures of the majority of governments to effectively curb corruption in their countries. In a region where countries run across a spectrum of most to least developed countries, CPI results question the effective and equitable distribution of resources needed to sustain the achieved growth.

The index, which covers 177 countries, scores countries on a scale from 0 (highly corrupt) to 100 (very clean). More than half of Asia Pacific countries score lower than 40.

Progress in Myanmar

The most significant change in this year’s index is the big improvement of Myanmar. Fifth from bottom in 2012, the country has gained six points and is now 19 places away from the bottom of the index. This is undoubtedly a reflection of the country’s opening up after years of military rule, and the benefits of introducing more transparent and democratic rules.

New laws are being reviewed, including ones on new media, anti-corruption and NGOs. The country has now ratified the UN Convention against Corruption. This trend holds potential for progressive benefits for the country’s people in the long run.

However, the long journey has just begun. The government still has much to do to bring its legal framework and regulations in line with acceptable standards, strengthen its anti-corruption institutions; and open up space for civil society and the media to monitor, and tackle corruption culture at all levels.

Corruption thriving in big economies

The emerging economic giants China and India have secured a poor score of 40 and 36 respectively. Despite its recent record of conviction for corruption, China’s score demands a holistic approach in tackling the issue.

In any nation, fighting corruption is not a task which merely rests within the parameters of the government. It requires the involvement of government officials, private sector and the civil society.

If genuine efforts are to be made, the present efforts of the Chinese government should go beyond observing the rule of law. They should embrace political reforms that would allow checks and balances, transparency and independent scrutiny together with acknowledging the role that the civil society can play in countering corruption.

India’s poor score is a reflection of an ironic situation: growth ridden with corruption. The state’s inability to effectively deal with petty corruption as well as the large-scale corruption scandals – which rocked the country over the past two years – continues to be the running theme. As a result, the monopoly of opportunities and inequitable distribution of benefits have stunted the government’s long efforts in battling poverty.

The story of people in Bihar fighting for recognition of their land ownership rights illustrates the uncertainty that rampant local-level corruption brings to daily life in economies which, on paper, are thriving.

India is likely to fall short of a majority of its targets in the Millennium Development Goals. Corruption in accessing basic public services – including health, food and fertiliser distribution, and education – as well as large-scale political corruption are significant contributory factors to the country’s appalling results in relation to poverty and hunger, gender equality and infant mortality indicators.

Together with India and China, the poor scores of other emerging markets in the region such as Thailand, Indonesia, Philippines and Malaysia indicate a lower level of competitiveness in countering corruption in comparison with their economic rivals in developed countries such as Germany, Japan, Canada and the United States.

Time for action

Unless serious counter measures are taken, the CPI scores forecast an adverse long-term impact on economic progress, fuelling people’s discontent with their governments.

The same principle applies to other countries such as Vietnam, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Maldives, Papua New Guinea, Cambodia and Timor-Leste, all of which boast significant economic growth over the past few years, yet fall far short in their efforts to devise an inclusive approach to fighting corruption.

If the prediction of an Asian-dominated 21st century is to become a reality, it is time for every government in the region to pay serious attention to the price of corruption, and the conspicuous and secretive modes in which it could take place. Thus sustainable development which embraces structural equality throughout the region can only be achieved with serious measures to counter corruption.

An unfinished bridge in southern Luzon, Philippines: if governments in Asia Pacific don’t prioritise fighting public-sector corruption to ensure resources go to where they were intended, economic growth will suffer.

Carousel image: Copyright, Transparency International / Maria Francesca Avila

Connect with us on Facebook

Connect with us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter

Follow us on Twitter