“I know I have a problem. It is all over the newspapers, everybody talks about it, but what can I do? I have no evidence. Can you bring me some evidence, please? Even better, just let me know what I shall do.”

– A minister of education during an OECD integrity assessment about efforts to fight corruption in his sector.

There is no doubt that corruption, in education or elsewhere, is bad and needs to be combated. The question is – how to do it best? What should those in charge go for, first?

Right after its inauguration in 2012, the then new Tunisian government reassured its electorate that it will continue to take the fight against corruption seriously and that it will not stop until the problem is “dealt with”.

drawing on articles from the

Global Corruption Report: Education.

Numerous international partners were asked to (re-)submit their recommendations, and soon enough the authorities’ to-do list became very long and very commendable. It revolved around better rules, better enforcement and more effective prosecution.

Enforcement and prosecution are important. Yet, once Tunisia included corruption in education in the list of things to deal with, it became clear that the success of anti-corruption measures would depend on solutions that are more sector-specific and that rely on analysis of sector policies and data.

In support of its quest for such solutions, the Tunisian government requested the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) to apply a novel methodology (featured in chapter 4.2 of the Global Corruption Report: Education) so that the integrity of the public education system could be assessed. This methodology would also enable the detection of policy shortcomings that create incentives for and open doors to malpractice, as well as suggest ways to address them.

What followed were weeks of elaborate data analysis, careful discussions with stakeholders, extensive reading of third party reports and mobilisation of OECD expertise to tackle a set of sensitive issues that often lacked transparency.

Loss of trust at the heart of it

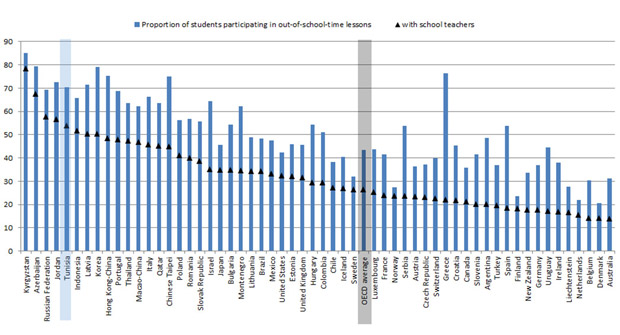

All strands of analysis, no matter how complex, pointed to a simple truth: malpractice in Tunisian education is driven by a loss of trust in what was once a proud and well-functioning public education system. For example, low standards of teaching during regular school hours leads to distrust in the ability of public schools to provide quality education. This nurtures the widespread practice of private tutoring, frequently by teachers from the same school (see the graph below), which becomes a precondition for passing grades.

As the graph shows, the share of total learning time in mathematics, science and language of instruction that takes place during out-of-school hours in Tunisia is among the highest in all countries that participate in the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA).

Similarly, in higher education the absence of integrity standards and of state-of-the-art systems of admission, accreditation and evaluation prevents students from enrolling in the subjects they are really interested in, and undermines institutional credibility and academic integrity. (Read more from this author about integrity standards in education here.)

Countries are ranked in descending order to the proportion of students participating in out-of-school-time lessons.

The OECD integrity report suggests that the first step in countering malpractice and corruption in Tunisian education should be the restoration of public trust in the education system – in its ability to deliver the quality and fairness that its stakeholders expect.

The main message of the report, however, holds true beyond the national borders of Tunisia: success in fighting corruption in education in any country will depend on the country’s ability to understand the root causes of the problem, and on its political will to address them.

Efforts in tackling corruption are set by the tone at the top, and must be driven by leaders who recognise the severity of the issue and are not afraid to act. Only then can public trust in the education system be restored.

Carousel image: Creative commons, Flickr / The Reboot

Connect with us on Facebook

Connect with us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter

Follow us on Twitter