On 24 July the town hall in Queimada Nova was packed. The citizens of this small town – which has about 8,000 residents and is situated 520km from Teresina, the state capital of Piauí – had gathered to listen to a group of volunteer anti-corruption activists who had just finished analysing the town’s accounts.

This was the first stop of the activists’ annual march to check up on public spending projects across this poor, arid state in the north-east of Brazil.

The citizens of Queimada Nova were shocked.

Just by looking at the town’s accounts, the volunteers had detected thousands of dollars of missing funds and improper receipts. They also showed the citizens how they discovered this.

Local student Lorenzo* was outraged after seeing the receipts from 2013 for bids on kilograms of mozzarella cheese and ham. “My school never got cheese. They just serve soup there.”

There were even receipts for bottled water, which, according to Lorenzo, never reached the students. “We get our water, which is pretty salty, from the tank or well.”

Regular check-ups

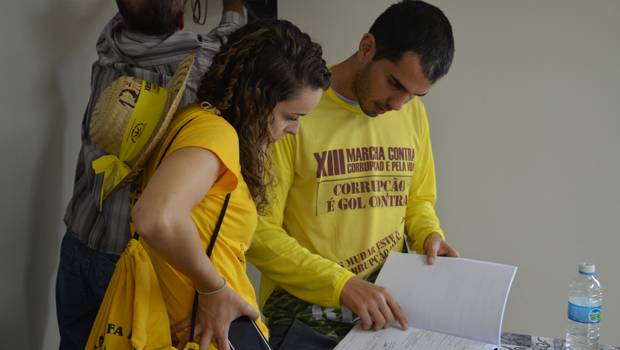

For the last 13 years, volunteers have come together for this Annual March Against Corruption and for Life. Organised by the NGO A Força Tarefa Popular and supported by Transparency International’s local partner Amarribo Brasil, the march involves a 120km trek over several days through various municipalities.

The volunteers make various stops to oversee public works, inspect state and federal projects, and give classes and lectures aimed at empowering local citizens to promote transparency and accountability.

Last year, we posted a series of articles following the marchers as they made their way through the state; this year, we decided to highlight the start of their journey.

Missing products

Clearly all is not as it should be in Queimada Nova. The volunteers found receipts for travel and lodging expenses which were not detailed or broken down; there was also money spent on buying food for schools, which students never got.

“We found numerous documents without justification. The people need an explanation,” said farm worker Thiago*.

When confronted with the receipts for the cheese, ham and bottled water, a spokesperson from the town’s Department for Education said these products were bought for teachers not students.

Health hazards

The volunteers also took a tour of the school canteens and kitchen units. “All the schools had hygiene and health problems and used expired products. In addition, there is also evidence of rodents and insects, both sources of diseases,” said Barbara*, a nursing student and volunteer.

During the day the marchers and residents also checked the progress and quality of municipal construction sites, armed with official documents and plans obtained through the Access to Information Act. In one instance, these showed that the town had received US$1.7 million to build a dam to help with the town’s water shortage and that a children’s pre-school was supposed to have been built with federal funds. Neither project had been completed. The town’s residents still need to buy water from trucks, which is low in quality and salty, and school never opened.

Where did the money go? The town received US$1.7 million to build a dam, but the project was never completed.

Besides the irregularities in the balance sheets and the unfinished works, there were also reports of nepotism among state workers. Alexandre*, a local worker, alleged that a town official appoints his family members to lucrative jobs: “His son, wife and brother-in-law are all working in the town hall and in other jobs appointed by the town leaders.”

Alexandre made a formal complaint to prosecutors, but so far nothing has happened.

Citizenship classes

There was also a training course for citizens on how to use the Transparency Portal for social control and civic audit, run by Amarribo Brasil and the Instituto de Fiscalização e Controle. The portal allows citizens to see the agreements of the federal government with the states and municipalities, including all money transfers that the latter receive from the government for projects, such as the pre-school and the dam mentioned above.

At the end of the day there was a public discussion of what the activists had found and a screening of the documentary made about the 12th March Against Corruption and for Life.

Though the volunteers only travel to Piauí once a year, the help they give makes a huge difference in empowering local residents to hold their elected officials to account.

For rural worker Luciana* popular participation is a must. “I’m not illiterate, but I do not know much about laws. So I wish more people who understood the meetings of the Board stood with us,” she said.

At the end of this year’s march, the organisers collated the complaints they had gathered along the 120km walk, and presented them to the responsible state and federal agencies, pressing them to address the issues.

What is certain is that the marchers will be back next year to check up and the citizens now have the tools to keep up the pressure for change.

* Names have been changed.

Carousel image: Lirian Pádua

Connect with us on Facebook

Connect with us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter

Follow us on Twitter