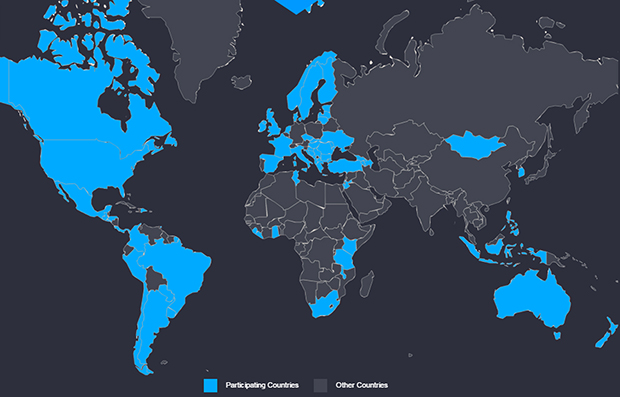

The Open Government Partnership (OGP) started with eight countries and now has 65 participating countries (highlighted in blue).

Since its inception in 2011, the Open Government Partnership (OGP) has sought to advance a vision of the world where governments are transparent, accountable, and inclusive. It is catching on. The OGP started with just eight countries and now has 65 who have agreed to share that vision and introduce practical ways to make it a reality.

For many of us working in the anti-corruption movement, transparency, accountability and participation have long been the key components of our toolbox to fix corruption, with public and corporate integrity being our ultimate aim. The “how” of open government and anti-corruption are largely one and the same.

We advocate greater access to information, for example, so citizens can hold their leaders to account and greater transparency so conflicts of interest in areas such as public procurement can be eliminated.

However, at the regional and national levels of the OGP, as well as in its assessments and cataloguing of the national action plans, the word corruption has been relegated to a small corner of the “word cloud.”

This is a problem because when nobody is talking about corruption in the open government movement, we overlook the challenges of making OGP work in countries where corruption operates.

In these countries private or corrupt actors do at least one of the following: bring undue influence into the political system, divert funds for development, weaken the power of critical oversight bodies, or just make it difficult to ensure basic services without bribes.

There are very few countries where none of these phenomena exist, if any. Not a single country on the Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index scores a perfect 100 and of the 65 OGP countries today, more than half score below 50 indicating an endemic problem with public sector corruption.

This is why it was so important that in his recent speech to the high level OGP meeting at the United Nations President Obama called on the OGP to expand its anti-corruption efforts and make working with civil society a key pillar. He declared that, “Continuing this global fight against corruption has to remain a central focus in the Open Government Partnership.”

In hallway conversations with fellow OGP advocates outside of Transparency International, when I question why corruption is not more central to the OGP, I am told that open government is about so much more than corruption.

Perhaps, but it ignores corruption at a cost, which is something Obama’s speech made clear: there is no real open government without a rigorous and effective anti-corruption regime in place. “Passing anti-corruption laws is necessary and then those laws have to be enforced,” he stressed, “so that those who steal from their people are held accountable and so citizens have faith that one system is not rigged and that justice will be done.”

Faith in the system will be much harder to generate if the open government agenda in any way diverts efforts and resources away from anti-corruption reform. It will be strengthened if the open government movement embraces anti-corruption as a key vector of its aims and architecture.

Why does this matter? As the US president forcefully noted, “Corruption is not simply immoral, from a practical perspective it can be used to siphon off billions of dollars that would be better spent promoting development. Corruption leads to inequality, it fuels human rights abuses, it strengthens organised crime and terrorism, and ultimately leads to instability.”

The OGP agenda neatly overlaps with Transparency International’s anti-corruption cause. If the OGP is to meet what it has identified as the five Grand Challenges – improving public services, increasing public integrity, managing public resources more effectively, creating safer communities, and increasing corporate accountability – it will need to tackle corruption head on.

To read this blog in Spanish, click here.

Carousel image: Screenshot from opengovpartnership.org

Connect with us on Facebook

Connect with us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter

Follow us on Twitter