The final two months of 2014 saw a surge of positive news for civil society whose collaborative and consolidated efforts over recent years to push for greater corporate transparency measures are now seeing the light.

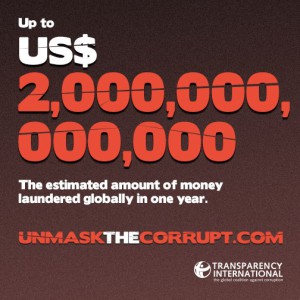

Civil society has called for greater light to be shed on the real living people who ultimately own or control companies – the beneficial owners. Current levels of secrecy mean that global detection rates for illicit funds by law enforcement are as low as 1 percent for criminal proceeds.

In 2014 the G20 rose to the challenge set by the G8 the previous year, adopting its own Beneficial Ownership Principles in November and thus corralling a much more diverse set of countries on the issue. Meanwhile the EU agreed on legislative reforms in December to require EU countries to capture this information in central registries and make it instantly accessible to law enforcement and government bodies and those with “legitimate interest”.

So it’s incredibly disappointing to hear that following a stock-take exercise last year, the Cayman Islands have decided to “continue its current method” when it comes to sharing beneficial ownership information, information which is essential in order to crack down on corruption and other illicit financial flows.

The UK British Overseas Territory has rejected the idea of setting up a public central register to bring together this information to facilitate access to law enforcement, a proposal that Transparency International, Global Witness and Christian Aid advocated for during the consultation.

Why no New Year’s resolution?

Some of the world’s largest secrecy jurisdictions are British Overseas Territories, including Cayman, the British Virgin Islands and Jersey.

In 2013, with the UK under international pressure, the Territories announced a series of consultations regarding their company ownership registration systems. Having information on who really owns companies is crucial to law enforcement, because shell companies are often used to launder the proceeds of crime including corruption and tax evasion.

Almost a year after the consultations closed, Cayman has been the first to make its results public. As it turns out, of the 43 responses received, 44% were from local companies, and 26% from local private sector bodies such as the Cayman Islands Bankers Association (curiously, the report classifies them as “local NGOs”).

Unsurprisingly, 70% of total respondents said that Cayman’s measures “are quite robust and are at a level of compliance beyond those of other jurisdictions”.

The government’s main conclusion? Cayman has no need to improve, as its current system is good enough.

But is “good enough” really good enough for citizens who are the victims of corruption and tax evasion?

In Argentina, for example, investigative journalists have uncovered evidence that millions of dollars in public funds have been diverted into offshore jurisdictions by allegedly corrupt businessmen with links to political power. The funds originally intended for much needed infrastructure projects ended up in bank accounts held by shell companies, including in the Cayman Islands.

This case is just one of the dozens of international grand corruption and crime cases which have been found to involve shell companies. Having critical information on company ownership publicly available to law enforcement when they need it and not many hours or days after they have submitted a request would greatly aid cross-border investigations. A UK government study estimated a public registry would save £30.3 million in police time alone.

Now that Cayman has decided to stay in the slow lane on beneficial ownership, doing the absolute minimum required to meet international standards rather than showing leadership, how will the UK respond if the rest of its Overseas Territories do the same? And will this satisfy other countries which are losing billions through tax havens, including the UK’s G8 partners such as China?

Connect with us on Facebook

Connect with us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter

Follow us on Twitter