In a blog published by the Bertelsmann Transformation Index, China expert Christian Goebel speaks about Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign and how it is helping transform China from collectivist one-party rule to a one-person authoritarian system.

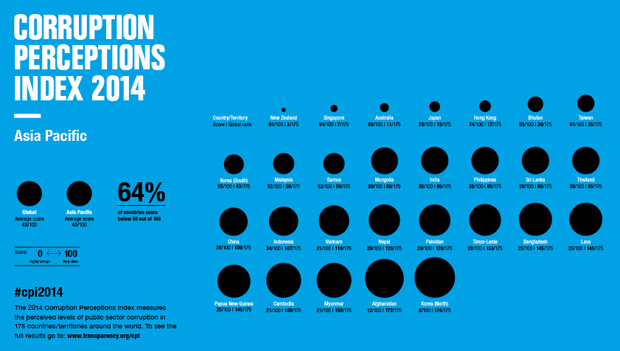

In Transparency International’s latest Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), China is among the countries with the largest decline in points, despite a high profile anti-corruption campaign that China’s president Xi Jinping launched in 2013. Is corruption getting worse in China?

I don’t think so. Once you start sweeping up dirt, people realise how dirty the room is. It is the same with corruption. China’s current anti-corruption campaign investigates people at all levels of government and in state-owned enterprises, and one finds corruption everywhere. So people see corruption getting worse, and the CPI is based on perceptions of corruption. I saw the same during my research on Taiwan: whenever the government prosecuted people, both the CPI and the Worldwide Governance Indicators’ Control of Corruption indicator would worsen – despite the fact that they were actually doing good work in Taiwan. So in some cases a decline in a corruption indicator might signal success in anti-corruption measures.

So the Chinese campaign is a success?

I would say that it has at least become more difficult to be corrupt in China. But has corruption decreased? I don’t know. Many people take the risk, and although the hurdles are higher, they are still corrupt. In China, we cannot measure actual corruption. We would have to ask people if they have engaged in an act of corruption, which Transparency International’s Global Corruption Barometer does. But such questions cannot be asked in China.

What kinds of people does the anti-corruption campaign target?

It targets everything – people at high levels and low levels of government, politicians and bureaucrats, universities and state-owned enterprises. The first politician to be investigated and prosecuted was the former deputy party secretary of Sichuan, Li Chuncheng. He was an ally of Zhou Yongkang, a former politburo member in alliance with Bo Xilai – who was rumored to be planning a coup to become general secretary of the Communist Party of China. This is the most comprehensive anti-corruption campaign since the party was founded.

Is it an attempt at reform or more a purge of Xi Jinping’s political enemies?

Probably both. The campaign fulfills a number of purposes. First, it aims to remove opponents of Xi Jinping or the regime. That has been obvious. Second, the campaign gives incredible power to Xi Jinping by enabling him to tear open factional networks and spread fear because many politicians in China are corrupt. It’s not so much a purge as a coup. Xi Jinping is putting himself at the centre of the party and minimising his dependence on other people. It’s a transformation from collectivist one-party rule to a one-person authoritarian system. Lastly, the campaign sends a signal that corruption is hurting the economy and society, and it must be reduced.

Apart from investigating and prosecuting individuals, does this campaign entail institutional changes?

Yes. A few examples: Anyone who works in public institutions now has to be more careful with spending; public servants have to use real receipts; grant money in universities cannot be taken as part of salaries anymore; and when the police collect traffic fines they have to record the transaction to prove that they are not pocketing the money. These institutional changes have mostly targeted petty corruption and administrative corruption. At a higher level, there are now stricter regulations on what politicians can do, what they can spend, and the amount of gifts they can give.

What other measures are needed to tackle corruption in China?

It’s hard for a system to reform itself from within without outside supervision. There is always a strong chance that corruption will come back once the campaign ends. Take Taiwan, for example. The Kuomintang, which was Taiwan’s sole ruling party until 2000, was rooted in corruption too. They tried to get rid of it but it didn’t work because at some point the party elites saw they were shaking the foundations of the party. The same thing could happen in China.

The China report of the Bertelsmann Transformation Index also points out that the lack of an independent judiciary increases the regime’s susceptibility to corruption.

The judicial system is very important. When an investigation finds irregularities in someone’s conduct that point to corruption, the case must be brought to court. There, judges must decide based on the evidence, not on which party the defendant belongs to. This is very hard to imagine in China.

Does the anti-corruption campaign foster support for the regime?

It increases support for Xi Jinping for the time being. People say let’s see what happens. If people feel betrayed or the campaign is deemed unsuccessful at some point, this might undermine public support of the regime. We saw this in 1989. People were hoping that things would get better under Deng Xiaoping and with a market economy. When the old habits came back, people started to protest and challenge the regime. But the relationships within the regime – between local governments and the central governments or across several departments, for example – are also a problem for political stability in China. Campaigns like these feed mistrust and fuel inactivity. People don’t dare take action anymore. It is undermining how the system operates for the time being. I’m certainly not against anti-corruption measures, and China’s campaign might work out, but it’s a very risky business that Xi Jinping is undertaking.

Carousel image: Copyright, Flickr / Eric Pesik

Connect with us on Facebook

Connect with us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter

Follow us on Twitter