There has been a big push in recent years to make government data open so citizens know where their tax money is spent– from snow collection in Chicago and broken street lights in Tbilisi, to what public officials declare about their assets in Mexico and their lobbying meetings with companies in the EU.

While data sets have exploded in number, only 7 out of 86 countries surveyed are disclosing key public data on their spending in a format that makes it accessible and meaningful for average citizens. Of all the countries assessed, only six per cent publish specific data about government contracts and only three per cent have public company registers that provide any information on who are the beneficial owners of companies.

We believe more governments should embrace open data because there is growing evidence that it leads to better decisions by government, and helps to deter corruption.

Having good open data on public procurement, for example, lets us know whether government money is being well spent or simply going to companies owned by public officials’ family members.

For Transparency International, knowing who is behind company ownership is key because you can then see if nepotism or cronyism is involved in the awarding of public contracts.

TI national chapters are working on the open data agenda in their countries to do just that.

In Slovakia, TI Slovakia has created the Open Public Procurement portal that covers over 36,000 contracts valued at more than €47 billion (US$52.6 billion)and which has historical data dating to 2009.

In searching the data, the chapter found in 2014 that four hospital contracts for catering services, worth €80 million (US$89.3 million), had been given to companies at prices that were up to 50 per cent higher than usual. Most of the money went to two companies, HCS and Dora Gastro, despite the fact that they had hardly any experience in catering. By partnering with journalists, a major media expose was published. As a result, three of the four directors of the hospitals were fired and a right-hand man of the minister of health, resigned.

In Lithuania, the chapter has worked with the National Courts Administration on a new online project, www.atvirasteismas.lt that provides information on how the judiciary works. Courts and judges can be compared against each other to see how well they are performing on basic criteria like the average duration of a case and the number of cases resolved by the courts. By targeting how well an institution is working, the site helps citizens to gain more trust in them as well as ask questions about why things are not working well – and to flag potential abuses of authority.

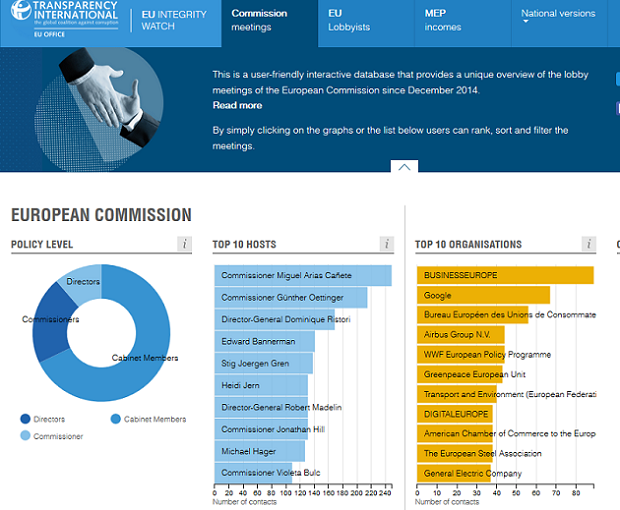

The Transparency International office based in Brussels that works on European Union (EU) issues has been able to pull together different open data sets on a site it launched call www.integritywatch.eu. The site serves as an online portal to collect and compare information about lobbyists that have registered in the EU and what they are spending as well as what members of parliament are reporting about their earnings from consulting work outside their parliamentary duties.

This data and the portal have helped to trigger a change in the behavior of European Parliament members (MEPs). Since the site was launched in 2014, revenue earned by MEPs in addition to their parliamentary work has fallen by over €1.5 million (US$1.68 million) annually and 100 outside activities previously done by MEPs have been stopped.

Making such links between open data and changes in behavior will be key if we want to see data trigger positive impacts for society, politics and our lives.

Connect with us on Facebook

Connect with us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter

Follow us on Twitter