Asia’s leading economies may be experiencing high levels of growth, but a lack of anti-corruption measures threatens fair distribution of wealth. Rukshana Nanayakkara, Transparency International’s Senior Programme Coordinator for South Asia, looks at the corruption challenges facing Asia’s emerging economies.

Asia’s leading economies may be experiencing high levels of growth, but a lack of anti-corruption measures threatens fair distribution of wealth. Rukshana Nanayakkara, Transparency International’s Senior Programme Coordinator for South Asia, looks at the corruption challenges facing Asia’s emerging economies.

The 2011 Corruption Perceptions Index results are a clear message to governments in Asia Pacific for stringent action to counter corruption. If the 21st century is to truly be Asia’s as predicted, comprehensive actions are needed to increase integrity and structural equality throughout the region. But to do this, governments and civil society must work together to counter corruption effectively.

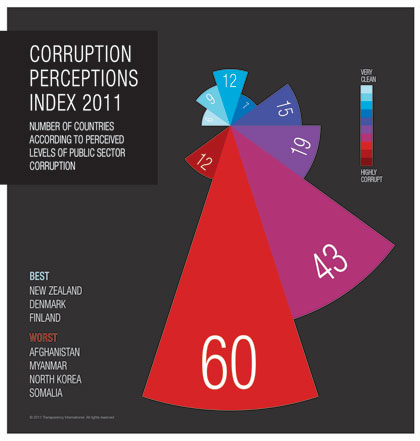

The release of the index reveals an alarming level of corruption in the Asia Pacific region’s public sector. The index, which covers 183 states, scores countries on a scale from 0- highly corrupt, to 10- very clean. The majority of countries in the region score lower than five, denoting a serious corruption problem.

Of these countries, quite a number appear at the tail end of the ranks. Although few countries, such as New Zealand, Singapore and Australia, secure places in the top 10, 16 countries in the region score below three. Among others, countries include Vietnam (2.9), Bangladesh (2.7), Philippines (2.6), Pakistan (2.5) and Papua New Guinea (2.2). Afghanistan, Myanmar and North Korea rank bottom globally, with scores of 1.5, 1.5 and 1 respectively.

The emerging economic giants in the region, China and India, rank 75th and 95th. This indicates a lower level of competitiveness in countering corruption in comparison to their economic rivals in northern developed countries such as Germany, Japan Canada and the United States. In China, greater economic freedom has failed to bring along a framework that hinders corruption, posing a serious challenge to sustained economic growth in the country. For example, recent research by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences states that since 1990, a number of high ranking government officials and senior managers of state-owned enterprises have fled the country with stolen assets worth US $123 billion.

The emerging economic giants in the region, China and India, rank 75th and 95th. This indicates a lower level of competitiveness in countering corruption in comparison to their economic rivals in northern developed countries such as Germany, Japan Canada and the United States. In China, greater economic freedom has failed to bring along a framework that hinders corruption, posing a serious challenge to sustained economic growth in the country. For example, recent research by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences states that since 1990, a number of high ranking government officials and senior managers of state-owned enterprises have fled the country with stolen assets worth US $123 billion.

Although India boasts a larger democratic space for public activism in countering corruption and opacity, little commitment has been delivered on the government’s part for substantive eradication. The scores reflect these inadequacies, and call on a comprehensive approach for counter measures.

According to figures from the International Monetary Fund, a number of other countries in the region such as Bangladesh, Indonesia, Maldives, Papua New Guinea, Philippines, Sri Lanka, Timor-Leste and Vietnam will see significant economic growth by the end of 2011. Nevertheless, these countries’ poor scores signify clear risks of corruption, resulting in unequal distribution of wealth and potentially lower investors’ confidence in the long run. If this pattern continues, the costs of corruption shall persist, leaving the possibility of both social and political unrest in the region becoming an ever increasing likelihood.

Connect with us on Facebook

Connect with us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter

Follow us on Twitter