Transparency International’s newly released 2011 Corruption Perceptions Index features some interesting results for the Americas. Alejandro Salas, Transparency International’s Regional Director for the Americas, takes a look behind the scenes. He discusses the trends, challenges ahead and the progress made in the region.

Transparency International’s newly released 2011 Corruption Perceptions Index features some interesting results for the Americas. Alejandro Salas, Transparency International’s Regional Director for the Americas, takes a look behind the scenes. He discusses the trends, challenges ahead and the progress made in the region.

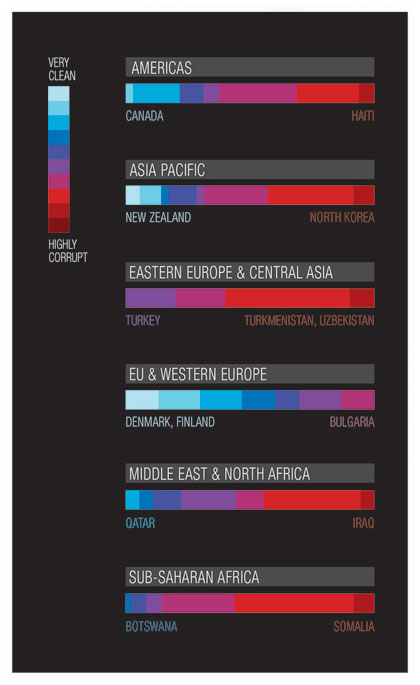

The 2011 Corruption Perceptions Index ranks 183 countries, 32 of which are in the Americas. More than two-thirds of them don’t even make it to the middle of the global ranking – indicating that corruption is a serious problem in those countries.

The 2011 scores refute arguments that blame corruption in certain regions on culture. Among the countries in the Americas that score above five we find countries not only from North America, but also from Latin America and the Caribbean. It is worth highlighting the case of Chile, a country that scores higher than the United States for the second year running.

Chile’s progress sends a strong and positive signal to other countries in Latin America. It raises the standard for those making efforts to advance anti-corruption and transparency related policies and practices. However, a relatively high rank should not be taken as cause for complacency. Although it is indeed recognition that things are moving in the right direction, countries like Chile and Uruguay should set themselves higher and more ambitious goals.

Chile’s progress sends a strong and positive signal to other countries in Latin America. It raises the standard for those making efforts to advance anti-corruption and transparency related policies and practices. However, a relatively high rank should not be taken as cause for complacency. Although it is indeed recognition that things are moving in the right direction, countries like Chile and Uruguay should set themselves higher and more ambitious goals.

At the other end of the ranking, you can find Haiti, Paraguay and Venezuela. These countries do not have a political system or ideology in common, but they all have weak democratic institutions.

Whether it is because institutions lack independence, or because democratic reform processes are still in their early stages after years of authoritarian rule, the fact is the main institutions in these countries are weak. This leads to greater opportunities for the misuse of public resources, for decision-making in favour of specific interest groups, impunity for criminals and vote buying in electoral processes. In other words, institutions are more vulnerable to corruption.

Another challenging group of countries includes Argentina, Brazil, Colombia and Mexico. These countries have abundant resources, relatively well-performing economies, some strong and modern institutions, regular elections and the rotation of power among different political parties. Yet, they continue to be stuck in the bottom half of the index.

Despite clear potential, these countries have been unable to move up significantly in the rankings over time. Part of the explanation could be that some of them have a federal or highly decentralised political structure.

Particularly in Brazil and Mexico, some modern institutions that push for reforms often clash with an old system based on patronage, cronyism and regionalism. So while showing progress and willingness to reform on several fronts, old practises still happen in different parts of their country.

A final word should go to highlight an issue that sadly affects too many countries in the region, namely organised crime. Illegal groups represent a very strong force that weakens a state’s institutions. For drugs, arms and human trafficking to take place, criminal groups need the security forces, the judiciary and other state agencies to remain weak. This results, for example, in criminals going unpunished by prosecutors and judges, and customs officials turning a blind eye.

Regardless of whether organised crime has weakened the state through corruption or if corruption has allowed organised crime to flourish, as long as both coexist, democratic institutions are under threat and corruption will not be averted.

I find it important to emphasise that analysing the Corruption Perceptions Index data is not about whether a country has a score of 0.5 more or less than a neighbouring country. The most significant thing here is to understand what the underlying factors that drive corruption are. This should inform decision-makers, so that eventually all countries in the Americas rank at the top end of the index.

Connect with us on Facebook

Connect with us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter

Follow us on Twitter