Laura Granado, Programme Coordinator in the Middle East and Africa Department, writes on the work of mobile Advocacy and Legal Advice Centres (ALACs) in Africa, bringing free legal advice to rural populations.

Laura Granado, Programme Coordinator in the Middle East and Africa Department, writes on the work of mobile Advocacy and Legal Advice Centres (ALACs) in Africa, bringing free legal advice to rural populations.

One of the main objectives of Advocacy and Legal Advice Centres (ALACs) is to empower the victims and witnesses of acts of corruption to exert their rights. Often, these victims or witnesses are illiterate, marginalised and extremely vulnerable – or sometimes simply people living in rural areas very far from legal infrastructure, who do not have real access to legal administrations.

ALACs in Niger, Senegal and Madagascar have organised more than 80 mobile ALACs, which have trained more than 7000 citizens from rural areas.

To give all citizens equal opportunity to benefit from the free legal advice of ALACs, mobile ALACs are organised each month in rural areas by our francophone African ALACs.

Mobile ALACs are an initiative that involves teams from urban ALACs visiting rural populations to offer them the same services that ALACs in town centres provide. They also train citizens on the law and other concepts related to the fight against corruption.

The organisation of a mobile ALAC starts with contacting mayors, village chiefs, and heads of the region, in order to arrange dates. Straight away, local community radio and local television networks (if they exist) are contacted to make sure that word gets out. Two “town criers” are also used to spread the message in public squares, in markets or in the community, for greater visibility and to mobilise local populations. In certain cases, a door to door approach is used to inform citizens of the date.

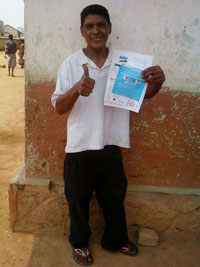

Usually citizens are very receptive to these actions. The arrival of a mobile ALAC signals a real event for villages, and is accompanied by activities like street theatre (based on themes that people encounter in their everyday lives) or music. But citizens are especially pleased to be given the opportunity to explain their problems and to finally be listened to, and to be supported in steps to resolve their cases.

The action starts with a training session including a public meeting on themes that matter to the local population – for example, corrupt practices in land management. The ALAC team informs citizens of legislation at their disposal (for example the penal code, the civil code, other laws relevant to public administration, and international legal instruments like the United Nations Convention against Corruption, amongst others) in order to buttress the fight against day to day corruption, and encourage citizens to reject corruption and to denounce all corrupt practices of which they are witnesses or victims.

The most frequent corruption problems that mobile ALACs encounter are land problems, problems associated with livestock theft, and traditional judgements that are fraudulent or abusive, amongst others.

After the training session, the legal counsellor and his or her assistants collect the complaints of citizens who are willing to share them. The consultations with the legal counsellor take place in a private room to guarantee the anonymity of the complainant. It is very important to give citizens from rural areas the opportunity to speak to a legal counsellor because usually they don’t have the means or the time to travel to the capital (sometimes hundreds of kilometres or many hours on the road) and also don’t have the means to pay a lawyer to help with their case. It should be added here that vulnerable populations are made up of those who do not have real access to justice. It is sometimes said that these people are “excluded” from access to justice.

At the end of each training session, t-shirts, key-rings or pens with the name of the ALAC printed on them are distributed to participants, in an effort to encourage populations to pass the ALAC’s message to friends or neighbouring populations.

Group of women for local development receiving t-shirts with the ALAC’s logo at the end of a mobile ALAC session in Kollo, Niger, October 2011.

Sometimes the mobile ALAC stays for more than a day, and the citizens who have talked to the legal counsellor are called in to bring the necessary documents to complete the dossier the next day.

The intended audience of a mobile ALAC is usually the general population, but some mobile ALACs are organised for a specific population – groups of women, for example. The fact that it is usually men who are given a public voice is a very strong cultural tradition in African countries that should not be forgotten. This can influence the decision to contact an ALAC, so it is essential that the mobile ALAC targets and sometimes trains groups of women, to involve them more in the fight against corruption. Other targeted populations might be college students or groups of young people.

Parents of students in training sessions of the Madagascar ALAC in schools, 2010.

Mobile ALACs are one of the many activities that our national chapters carry out to strengthen the rural populations of African countries, and to increase interest and civic responsibility in the fight against corruption. See also:

Citizens pose questions on corruption during a mobile ALAC session in Ambatondrazaka, Madagascar in August 2011.

This translation was provided by Rosie Slater, press intern at Transparency International. The original blog post can be accessed here.

Connect with us on Facebook

Connect with us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter

Follow us on Twitter