The following was written by Mark Worth, Transparency International’s Whistleblower Programme Coordinator, and Christian Humborg, Managing Director of Transparency International Germany.

In a country where whistleblowers have helped expose poor care in a nursing home, dioxin-laden livestock feed, inadequate emergency services in hospitals, rotten meat, and mad-cow disease, one would think – and certainly hope – that people who call attention to such scandals would be completely protected from all types of retaliation.

In Germany, they are not.

Looming over Germany are two international commitments that compel the country to act. It has a long road ahead if it wants to meet the G-20’s deadline to implement whistleblower protection rules by the end of 2012. Germany also has yet to comply with the Council of Europe’s Civil Law Convention on Corruption.

As the debate over whistleblower protection continues in Germany, such laws are becoming more commonplace in all regions the world. In the past few years alone, new or strengthened whistleblower protection legislation has been approved or proposed in many countries, including Australia, Chile, India, Ireland, South Korea, Switzerland and the US.

Federal lawmakers have discussed strengthening protection for whistleblowers on-and-off over the past few years. In 2008, the Christian Democrats proposed certain protections for whistleblowers in the private sector, but the reform stalled.

On March 5, lawmakers took up the issue again at a hearing held by the Bundestag’s Committee for Labour and Social Affairs. Experts invited by Germany’s five main parliamentary factions offered their opinions about whether the country’s current laws adequately protect whistleblowers from firing, harassment and other types of retaliation.

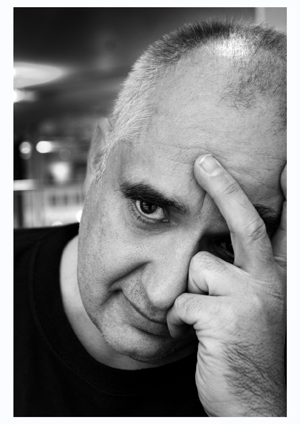

Guido Strack is the founder of German non-profit organisation Whistleblower Netzwerk and a whistleblower himself. His case and others will be shown in a photographic exhibition of the Whistleblower Netzwerk in the European Parliament in Brussels, 26-29 March. Photo: Petrov Ahner

As they now stand, German laws protect public employees to some extent, and employees of private companies theoretically have certain, narrow protections if they blow the whistle. But the legal landscape is far from comprehensive and far from clear, as several of the experts confirmed.

Among those on the “pro” side was Guido Strack, founder of Germany’s Whistleblower Netzwerk. Himself a whistleblower who exposed cost overruns while working at the European Commission, Strack said Germany needs “clear legal protection so that whistleblowers can know what to expect” when they come forward.

Joining Strack was Cathy James, chief executive of the London-based whistleblower organisation Public Concern at Work. James said the group has been instrumental in helping people come forward under the UK’s Public Interest Disclosure Act, one of the world’s premier whistleblower protection laws.

Allaying German lawmakers’ concerns that a strong whistleblower law might lead employees to immediately take their concerns to outside agencies before trying to work them out with management, James said 95 percent of cases her group has handled over the past 10 years were handled internally.

Though the momentum is growing throughout the world to strengthen whistleblower protection laws, Germany’s business establishment seems to be opposed to making substantive reforms.

Among them was Roland Wolf of the Federal Union of German Employers’ Associations (BDA). He called a 2011 ruling by the European Court of Human Rights, which found that Germany interfered with a nurse’s right to freedom of expression when she was fired from a nursing home for exposing mistreatment of elderly people, “strange, at the least.” Wolf added that the ruling does not mean that Germany must change its whistleblower laws. Even still, the case does send a strong message to German employers about responding to whistleblowers.

Josef Winter of Siemens said the company is handling anti-corruption issues on its own terms – having set up a “Compliance Helpdesk” where violations can be reported, and by hiring an ombudsman, an external lawyer who employees can speak to for free.

It was disappointing, however, to hear another Siemens representative, Klaus Moosmayer, cast doubts upon the need for stronger whistleblower laws. He questioned whether they could succeed because it would be difficult to keep a whistleblowing employee at a company after he or she had been exposed.

Connect with us on Facebook

Connect with us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter

Follow us on Twitter