After four years of economic crisis and financial scandal, finally some good news.

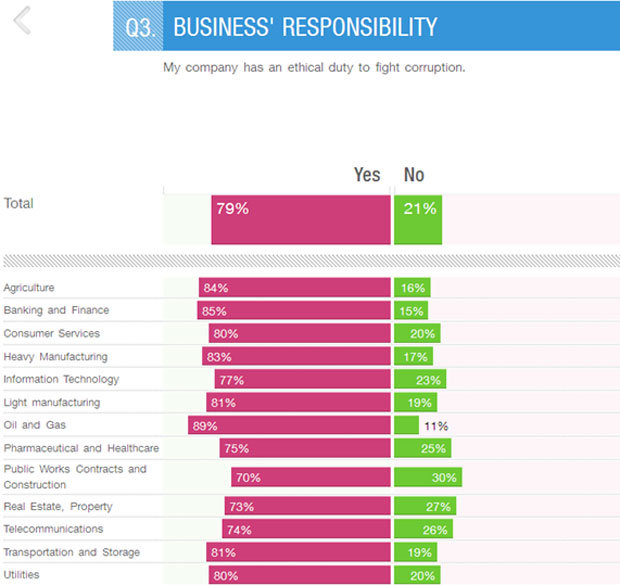

Eighty-five per cent of bank employees surveyed believe that their companies have an ethical duty to fight corruption. That is a finding from our survey of 3,000 businesspeople in 30 countries: Putting Corruption out of Business (see what businesspeople from other sectors and countries thought here).

Laws and standards alone will not bring sustainable change to the private sector. Pressure for institutional change must also come from within organisations, both at the leadership level and among employees. So these numbers are encouraging.

For good reasons, the banking sector remains a prime target of calls for more ethical behaviour in business conduct. The ever-expanding LIBOR scandal is just the latest in a series of events showing that a lack of integrity is endemic in the financial system.

In the late 1990s senior executives at Fannie Mae (the US government-backed institution that is supposed to help people secure loans to buy houses) engaged in systematic misstatement and manipulation of earnings in order to trigger pay bonuses.

These and many other disturbing examples show how corruption in the form of fraud and reckless pursuit of profits, undue influence over regulators and conflicts of interest has infected the financial system. While the financial crisis is the result of many factors, lacking transparency is an integral part of the story. And without this understanding we cannot tackle all the root causes of the financial crisis.

Most recently, Transparency International’s ranking of corporate transparency found the financial sector scored poorly.

Is there some light at the end of the tunnel? Has some of the pressure to improve integrity in the financial sector paid off?

A change in Germany?

Two weeks ago Deutsche Bank CEOs Jürgen Fitschen and Anshu Jain presented their new corporate strategy. They spoke of their commitment to initiate a cultural shift in the organisation. Fitschen said that colleagues who want to become rich quick are no longer welcome at Deutsche Bank. They are even reconsidering their slogan “Passion to Perform / Leistung aus Leidenschaft”.

It seems that Deutsche Bank has discovered the business case for ethical behaviour. But given that these statements come from two major protagonists of an era of exorbitant growth targets and bonuses, serious doubts remain whether we can take them for granted.

More concretely, Deutsche Bank committed itself, for example, to reducing bonus payments in relation to business performance. Bonuses for top management will also be made as a single payment after five years rather than staggered payments over three.

However, more concrete and measureable targets need to follow in order for the public to be able to assess whether the company is making progress on ethical commitments.

Peer Steinbrück, former German Minister of Finance from the Social Democrats and currently the likely challenger to Angela Merkel in the 2013 Parliamentary Elections [Editor’s note: shortly after we published this post, Steinbrück was confirmed as the SPD candidate for chancellor], did not seem very impressed by Deutsche Bank’s new strategy. Two weeks after the launch he presented his new concept to regulate the financial sector – including a plan to force the bank to separate their investment from the credit business.

The proof is in the pudding: it remains to be seen whether appropriate action will follow or whether these commitments will turn out to be mere window dressing.

Making integrity central to business

Public commitments accompanied by clear targets for ethical conduct give us the means to hold institutions accountable. We have to monitor their progress and keep reminding them of their promises.

Because one thing is for sure: Financial institutions need to introduce integrity into all their practices. And if customers, investors and employees vote with their feet, they make integrity the more profitable long-term strategy.

Connect with us on Facebook

Connect with us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter

Follow us on Twitter