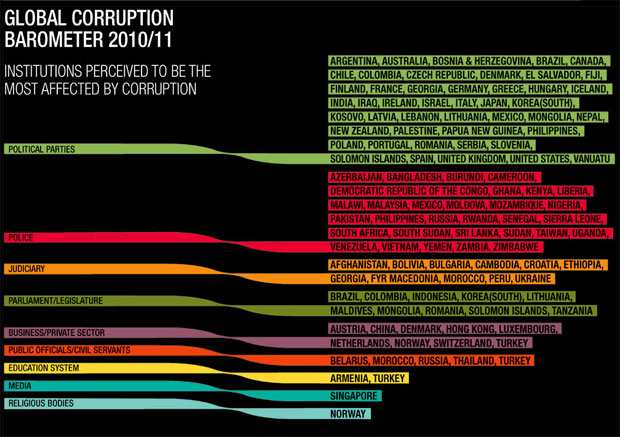

Corruption in the police force is the top corruption issue for citizens in many countries across the world. In 31 of the 100 countries covered by our global survey, people told us the police are the most corrupt institution in their country.

Every day around the world, too many people are stopped by the police demanding a bribe. They then face the following dilemma: Pay the bribe and you not only lose money, you encourage the policeman to ask for another bribe, and undermine the rule of law. Refuse to pay a bribe to a policeman, and they won’t help you, or worse, you risk intimidation, perhaps even violence.

But how do you stop this incident from happening? How can you tackle corruption among the people who are supposed to be preventing it?

We have looked at efforts to stamp out corruption in the police in ten countries, from the Wood Commission in New South Wales, Australia that showed that corruption was systematic, and not limited to “rotten apples”, to Afghanistan, where 25% of Afghan citizens had to bribe the police despite $29 billion spent on training and equipment.

Shakedowns and ‘Cultures of Silence’: Defining police corruption

Our new report, Arresting Corruption in the Police, presents corruption risks in police forces and examines the mixed success of reform efforts in ten countries.

The Transparency International Defence and Security Programme has had great success in developing a typology defence sector corruption and using this as a starting point for discussion with the armed forces and civil society in a number of countries, allowing people to discuss in detail a subject which is normally taboo.

This same approach has been taken in our new report, examining previous typologies, and presenting a new police corruption risk typology, complete with definitions (pages 26-27). With this, we hope that the report works on not only for comparative examples, but also acts a practical tool for those in the police and civil society who want to push for reform.

In the report, we use the typology and look at stories of police reform failure and success. In China, efforts failed because they did not secure long-lasting change. Instead they were focused on superficial measures against individual officers – the “bad apple approach”.

Georgia had more success when, in a dramatic move, 16,000 police officers were dismissed and salaries quadrupled for the remaining force. The entire traffic force (30 000) was fired and a new one rehired.

Civil Society helping citizens confront police corruption

The report’s principal conclusion is that civil society has done too little to drive reform. There is a huge need for civil society to engage more with the issues of police corruption and reform.

Civil society organisations can be powerful tools not only in channeling public outrage of police corruption, but also in identifying concrete actions to be taken towards reform.

In preparing the report, we identified great examples of how civil society has pushed for reform of the police and involved citizens in doing it.

Transparency International Russia ran an online campaign that influenced the content of police reform legislation.

They then made sure that the public knew what the new laws meant, particularly the fact that the police, viewed as the country’s most corrupt institution, are obliged to display identification at all times. See them take to the streets to challenge police officers to show their badge here.

Similarly, Altus, a global network of local NGOs, takes citizens to visit their local police stations and score them. The scores are then used to propose and drive reforms. During the most recent police week, 1044 stations were visited across 20 countries including the U.S.A., Brazil and Nigeria.

We hope that this report proves to be a useful tool to help those who want to tackle police corruption, both from within and outside the police, and creates debate on good approaches. Let us know what you think!

Connect with us on Facebook

Connect with us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter

Follow us on Twitter