Two years ago a doctors’ strike threatened to paralyse Slovak healthcare. Over the previous years, healthcare expenditure in Slovakia had already risen to nine per cent of GDP. And while inefficiencies were widely suspected, the overall message from the strike seemed clear: Slovak healthcare needs more funds. Then at TI Slovakia we calculated that 21 per cent of all healthcare public procurement expenditure could be saved if more competition was introduced into tenders.

These savings would allow for a 10 per cent increase of doctors’ wages, maybe making them less susceptible to corruption (almost one Slovak in three has reported paying bribes when coming into contact with the health sector). And we helped shift the conversation from the need for more funds to the potential for savings.

Transparency is the first step

To shed more light on the notoriously corrupt healthcare procurement in Slovakia, we collected and analysed data from tenders worth €800 million, all larger purchases over the period 2009 – mid 2012.

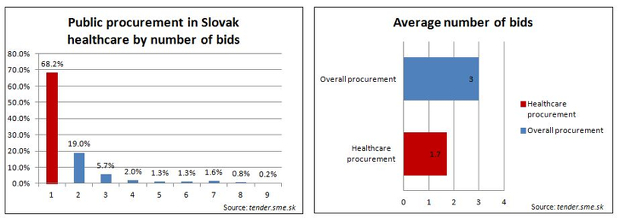

The results were startling: more than two-thirds of all money was spent in tenders with a single bidder. An average of only 1.7 companies bid in healthcare tenders, while the average number of bids in all Slovak procurement reached 3. Slovakia’s three largest hospitals rarely conducted a tender that attracted more than one offer. Many suppliers came from tax havens.

A case study of purchases of CT x-ray machines confirmed our findings. Two-thirds of 27 CT scanners bought over the previous five years were purchased without competition, although four suppliers were on the market. “Once a tender is announced, you know who will win,“ a supplier told us. As a result, a Slovak hospital paid €2.8 million for a CT scanner, which a Czech hospital bought for half the price.

No competition means higher prices. If the number of bidders in all single-bid tenders would increase from one to just two, €35 million or 21 per cent of all procurement expenditure could be saved. One explanation of the poor state of competition is the particularities of healthcare. Another likely explanation is rampant corruption.

Corruption in your healthcare probably deserves attention too

Studies suggest the healthcare sector is particularly prone to corruption. The already messy interaction of patients, doctors and hospitals, insurance companies, pharma and technology suppliers, and state regulators is all the less transparent due to major information asymmetry. Sixty three per cent of Slovaks told Transparency International’s Global Corruption Barometer 2013 that they thought the health system corrupt.

Just like in Slovakia, around the world healthcare costs are going through the roof. In OECD countries health expenditure averaged 9.5 per cent of GDP in 2010. And just like in Slovakia, corruption is common. In Europe, one in three people believe that corruption is widespread. It has grave consequences. With corruption, access to care, as well as its quality, plummets.

This puts healthcare actors under increased pressure to behave ethically. Perhaps that is why although corporate funding is very rare in Slovakia, we managed to secure €35,000 worth of private sector donations and launched a project aimed at bringing more transparency into healthcare.

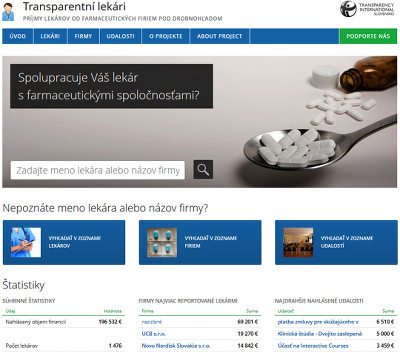

Modeled on the US Dollar for Docs website, we created Transparent Doctors, a web portal, which allows users to look up information on doctors’ collaboration with pharmaceutical companies. By 2016 similar information on the relationships between pharma and doctors should be available in 33 European countries.

And what is next? To increase our impact we plan to launch a Healthcare Anti-corruption Hotline for reporting petty corruption, mismanagement or fraud. While helping those affected by corruption in often life-threatening situations, it will also help us better understand the intricacies of corruption in healthcare.

Carousel image: Creative Commons, Flickr / damiandude

Connect with us on Facebook

Connect with us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter

Follow us on Twitter