Without strict enforcement of anti-graft measures, corruption runs rampant – just like traffic that skips a red light.

Imagine a scene in Buenos Aires, Caracas, or any other capital city in the Americas: It is 10:30am and you are in your car rushing to an appointment for which you are already late. You are at a red light. You look to the right, no cars coming, look to the left, no-one. You can cross the red light or wait. What do you do?

In an ideal world, a red light should be enough to prevent you from crossing the junction. However, in practice this ordinary traffic situation shows you can either break the law to gain some time or follow the rules and wait.

Your decision is probably influenced by several factors, for example, how important the appointment is. But let’s focus on the decision being based on the likelihood of getting into trouble. With no cars or people near you, the possibility of an accident is marginal; therefore your only other main worry is that you get caught crossing the red light and consequently have to pay a fine (or a bribe). This has an impact on your pocket and makes you waste even more time.

Just as this simple example illustrates, even good infrastructure – in this case a red traffic light – has limited effect if you feel you can get away with breaking the law and go unpunished. A similar thing happens with anti-corruption measures like transparency laws, anti-corruption plans and agencies, codes of ethics, the signing of international anti-corruption conventions, registers of interest and asset declarations by public servants, and many more. All those constitute fundamental infrastructure for preventing corruption. They are essential, but not enough.

Infrastructure there, but results still poor

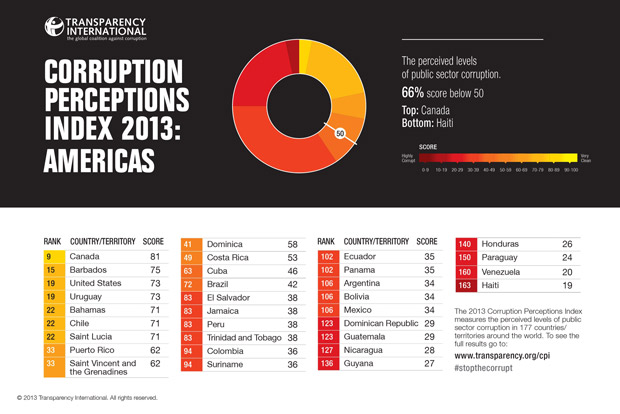

Several countries in Latin America and the Caribbean have made commendable progress in setting the infrastructure for fighting corruption: 21 countries in the Americas have access to information laws; 31 countries are signatories of the Organisation of American States Convention Against Corruption; and 17 countries are participating in the Open Government Partnership. This deserves praise and encouragement. So, why is the Corruption Perceptions Index in its 2013 edition still showing poor results for the region?

Take a look at the 39-point average score in Latin America on a scale where 0 is perceived to be highly corrupt and 100 very clean. The region fares only slightly above the Middle East and North Africa average score (37) and that of Sub-Saharan Africa (33), and way below the 66-point average score of Western Europe.

Electoral democracy and governance efforts have been a feature in parts of the region for many years, and rules and institutions to support both have been created. Why can’t we see great progress when it comes to fighting corruption? Remember the red traffic light.

I believe the answer is clear. We can spend a lot of effort building infrastructure, but when we have drugs and weapons worth millions of dollars crossing borders every month (even elephants have crossed the Mexico-US border illegally), corruption remains rampant. Local examples of this are the thousands of citizens paying bribes to the police in Bolivia, vote-buying and the use of public resources for electoral purposes in Venezuela, and politicians who keep hiring family members to government positions as recently illustrated by Paraguayan senators.

In other words, you can install all the traffic lights you want in a city, but if no real mechanism is in place to enforce the “stop” when the red light is on, then they will only be part of the urban landscape, mere decoration.

Guatemala slipping down the ranks

So, no big surprises for the Americas in the Corruption Perceptions Index 2013: the situation is still dire in too many countries. Most worryingly, in Central America there is even a downwards trend. Most countries in that region are moving slowly but surely down the ranks of the index.

Central America’s 2013 champion in walking backwards, Guatemala, falls by four scores and 10 ranks as it is increasingly becoming a strategic location for organised crime, and its population is consequently suffering from extreme violence and insecurity. Opaque private interest groups are undermining the institutional set-up in the country, making corruption a daily affair. The huge paradox is that President Pérez Molina declared 2013 as the Year of Transparency.

Needless to say, corruption is also a feature in North America. While the US’ rank stagnates, Canada’s score goes down by three points this year. In order to prevent its score from slipping further downwards in coming years, the country needs to continue to strengthen its anti-corruption infrastructure and enforce its use. In other words, flash the red light and make sure those who violate the law are captured on camera and a fine is mailed the next day. There is no justifiable excuse for the US, the world’s leading economy and one of the oldest democracies, not to be among the top three performers in the Corruption Perceptions Index.

Enforcing anti-corruption frameworks and ending impunity for corruption is not only a job of a few public servants or lawmakers. It requires political will from the top, from all political camps and a strong belief from citizens that corruption harms us all and can be stopped.

Personally, I don’t want to live in a city where traffic lights don’t work. Accidents, blood and broken glass, chaos, and unpredictability would result. In the same way, I don’t want to live in a country where corruption runs free.

Carousel image: Copyright, Transparency International / Alejandro Salas

Connect with us on Facebook

Connect with us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter

Follow us on Twitter