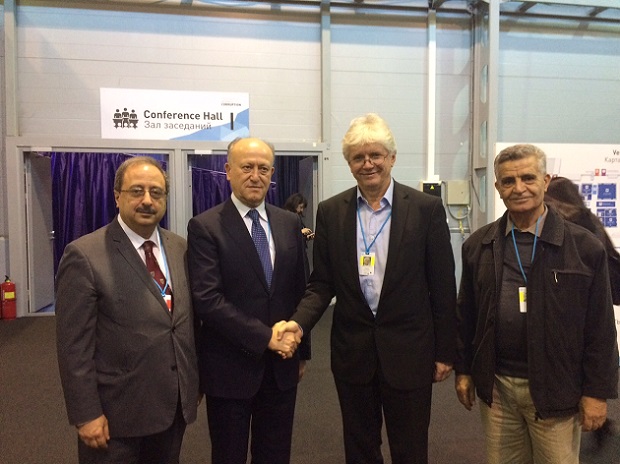

Ashraf Rifi, Lebanese Minister of Justice (2nd from left) and Miklos Marschall, deputy managing director of Transparency International shake hands on the UNCAC Review Transparency Pledge at the Conference of States Parties to the UN Convention against Corruption. Ghassan Moukheiber, Lebanese Member of Parliament (on left) and Dr. Azmi Shuaibi of Transparency International Palestine (on right).

14 December 2015 marks ten years since the landmark UN Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) came into force. UNCAC represented the first truly international consensus on the importance of tackling corruption at all levels and it explicitly identifies the important role that civil society plays in holding governments to account.

To make this happen, UNCAC recognises that governments must take appropriate measures “to promote the active participation of individuals and groups outside the public sector, such as civil society… in the prevention of and the fight against corruption”.

To this end, UNCAC explicitly recognises that civil society needs to be free to seek, receive, publish and disseminate information about corruption. In practice, this means that every country should have access to information laws and should protect the rights of citizens to blow the whistle on corruption.

UNCAC’s acknowledgement of the intersection between addressing corruption and ensuring the inclusion of civic groups to ensure better government accountability and transparency was reiterated in the new UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) agreed by governments in September 2015. These explicitly say that “the need to build peaceful, just and inclusive societies … are based on respect for human rights…and on transparent, effective and accountable institutions.”

This is enshrined in SDG Goal 16, which calls on governments to stamp out corruption and bribery and indicates that transparency and public accountability are crucial enablers of sustainable development.

Civil society action to tackle corruption

As the world begins to look towards strategies to ensure the implementation of Goal 16, Transparency International’s new report, released today, Civil Society Participation, Public Accountability and the UN Convention Against Corruption shows that civil society actors have long been at the forefront of efforts to promote and protect human rights through their work to fight corruption.

Right to information campaigners have made headlines across the world for their activities in shining the light of transparency on public corruption; whistleblowers and their civil society supporters have taken risks to expose and prosecute corruption. Activists from India to Dominican Republic to Mexico have famously used the right to information to access documents from their governments proving public corruption in welfare distribution, access to basic public services and the award of infrastructure contracts.

The dark side of the success civil society has had fighting for people’s rights has resulted in increasing persecution and resistance from entrenched government and private sector interests. As the new report illustrates, anti-corruption organisations across diverse jurisdictions are being targeted.

In Kuwait and Russia, for example, governments have attempted to shut down non-governmental organisations (NGOs), including Transparency International chapters, working on corruption on national security grounds.

In Cambodia and Venezuela, tough laws have been passed which will likely have the effect of severely restricting the ability of anti-corruption bodies to establish and operate in-country.

The UN Special Rapporteur’s 2015 Situation of Human Rights Defenders report said: “Defenders working on governance issues, promoting transparency and accountability on the part of States, and combating corruption are among the most at-risk groups of defenders, subject to relentless harassment and multiple types of threats and attacks … These defenders reported governments’ reluctance to protect them, due to the numerous political and economic interests at stake.”

The media have been a crucial partner in the fight against corruption, taking on serious personal risk to expose wrong-doing at the highest political levels. Since 1992, 477 journalists have been killed for investigation corruption and human rights abuses, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists.

Much-needed protection

Anti-corruption activists must be protected and respected if both their rights and the rights of those for whom they are fighting are to be safeguarded and entrenched. Unfortunately, we do not see this happening. Official resistance to civil society’s involvement in anti-corruption efforts by governments continues despite our best efforts.

At the recent UNCAC Conference of States Parties in St. Petersburg in November, governments once again endorsed the exclusion of civil society organisations from engaging effectively with the key UNCAC review and implementation mechanisms, even though civil society were allowed to make the case at the meeting for more systematic inclusion. This is a disappointing outcome considering that public accountability and anti-corruption are two faces of the same coin.

2016 will mark the beginning of the next cycle of the UNCAC Review Process. The goal of civil society is to proactively engage with, and be engaged by, governments throughout the review cycle to ensure it is more transparent and participatory.

It is imperative that the next cycle be used to show that for both UNCAC and the SDGs to have an impact, these frameworks must explicitly acknowledge and protect people’s human rights by tackling the corruption, which diverts much-needed resources that could be better used to provide services and protect rights.

The UNCAC Coalition, a network of more than 300 civil society organisations, is calling on countries to sign up to an UNCAC Review Transparency Pledge, which includes embracing the role of civil society throughout implementation of the Convention. So far 20 countries have publicly supported the pledge, including Lebanon (see photo) and a growing number of countries are beginning to understand that if you are serious about fighting corruption, you need to include citizens.

Corruption represents a breakdown in trust between people and their governments. To ensure corruption is eradicated, people – whether in their role as public servants or as citizens – must be at the heart of our efforts to rebuild that trust.

Connect with us on Facebook

Connect with us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter

Follow us on Twitter