Deborah Hardoon, Transparency International’s Senior Research Coordinator, explains how the Corruption Perceptions Index measures corruption and how this can be an incentive for tackling it.

Deborah Hardoon, Transparency International’s Senior Research Coordinator, explains how the Corruption Perceptions Index measures corruption and how this can be an incentive for tackling it.

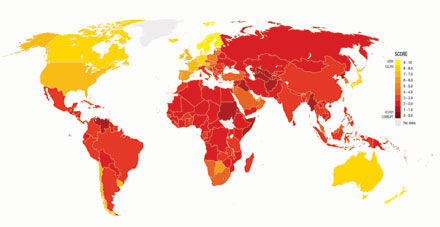

Since 1995, the Corruption Perceptions Index has scored and ranked countries from all around the world according to perceptions of the extent of corruption in the public sector. The simplicity of giving each country a single score has enabled the index to be a powerful awareness raising tool with global reach. The index provides a valuable insight in terms of how the extent of corruption can vary around the world. It also generates data which can be mapped and modeled to enhance our understanding of the relationship between corruption and other important outcomes. And as a single number cannot describe the full complexities and dynamics of corruption and its actors, it also paves the way for further and deeper analysis.

A measure of perceptions: As an individual, you might know of an incidence of a bribe being paid to a policeman for example, and exactly how much that bribe cost.

Or you may have read in the papers news of corruption in a particular government procurement contract. But cases of corruption, that we know or have evidence of, make up just a fraction of the full extent of corruption across society.

Corruption is by its very nature deliberately hidden, and being able to obtain information about particular cases depends on freedom of information, the quality of anti-corruption legislation and the effectiveness of the laws and institutions in terms of holding guilty parties to account.

Given the fundamental challenges of gathering evidence based data on corruption, the Corruption Perception’s Index takes a different approach. This index brings together a number of different data sources (in 2011 we use 17 separate surveys and assessments), which capture perceptions of the extent of corruption in the public sector of a country/territory. With this approach, in 2011 we are able to score and rank 183 countries/territories from around the world on the same scale.

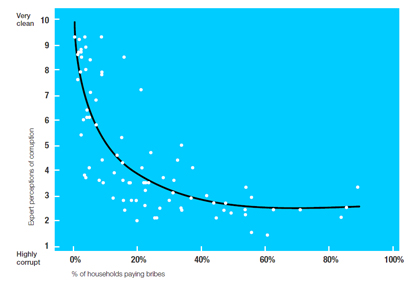

Perceptions data has been shown to correlate very well with other indicators that use a more evidence based approach. For example, Transparency International’s Global Corruption Barometer 2010 asked people from 86 countries whether they had paid a bribe for public services.

When these results were plotted against the index scores for each country, we can clearly see that ordinary people are more likely to have to pay a bribe to access basic public services where corruption is perceived to be more prevalent.

People’s experiences of bribery in the 2010 Barometer compared to experts’ perceptions of corruption in the 2010 Corruption Perceptions Index.

What the data can tell us: The CPI 2011 allows us to compare 183 of these countries against each other. We can highlight at the global and regional level where countries and territories have been successful in controlling corruption. Looking at South America, Chile and Uruguay clearly stand out as having public sectors that are perceived as less corrupt than their neighbouring countries.

In Africa, we can point to Botswana, which is ranked as the cleanest country on the continent. Highlighting these differences and drawing attention to good country examples can be a powerful incentive for other countries to actively fight corruption and improve their relative position.

In contrast, at the bottom of the index, we find Somalia, a country ravaged by war and famine, and North Korea, a country with one of the worst human rights records in the world. Governments, businesses, and civil society in countries towards the bottom of the index should do all they can to fight corruption and pull them up and away from the bottom of the Corruption Perceptions Index.

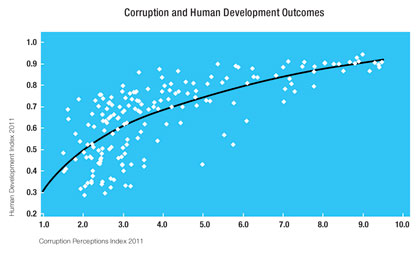

At a macro level, the index can also be used to illustrate the relationship between the extent of corruption and other important outcomes. We can plot the Corruption Perceptions Index against the UN’s Human Development Index, and find that where there is perceived to be more corruption, human development outcomes tend to be lower.

Transparency International’s Bribe Payers Index (BPI) captures perceptions of the likelihood of companies to pay bribes when doing business overseas and the 2011 edition finds that in countries where the Corruption Perceptions Index scores are low (highly corrupt) companies from these countries are seen as more likely to pay bribes when doing business overseas.

Quantitative data is a great tool. We can paint maps and plot graphs of relationships, but it is also important not to stop at the score in the Corruption Perceptions Index when assessing corruption, but rather see it as a starting point for a more detailed exploration for a given country, sector or institution.

Understanding how corruption manifests itself in its many forms and as perpetrated by various actors, both those on the demand and the supply side require a much more detailed analysis and a host of diagnosis and assessment tools.

Connect with us on Facebook

Connect with us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter

Follow us on Twitter