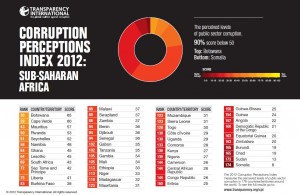

What can we do to fight corruption? One of the most frequently asked question Transparency International got when we published the Corruption Perceptions Index 2012 last week.

The question is especially pertinent in Africa, which only has five countries in the top 50 countries on the index, where lower scores indicate a greater perception of public sector corruption in 176 countries. 90% of African countries on the index score less than 50 out of 100, with Botswana in 30th place showing what can be achieved in the fight against corruption, and Somalia in last place warning what happens if you don’t.

Corruption is a daily burden in Uganda, which ranked 130th out of 176 countries, and has recently faced a major aid scandal. The situation is particularly tense in the health sector. Our research has shown that less than half of staff were available at health facilities. The absence of health specialists inevitably exposes people to paying bribes if they want preferential treatment.

Indeed, 24 per cent of health providers we surveyed acknowledged that taking informal payments in exchange for services is common. 44 per cent reported that service users sometimes offer gifts to health workers. (Our colleagues in Zimbabwe face a similar challenge: nurses once fined women for screaming during labour).

The situation is aggravated by the lack of transparency and accountability, making it harder for citizens to tackle the problem. None of the lower level health facilities we looked at had complete financial records, and most facilities did not have updated drug stock registers.

In 2010 we set out to address corruption problems in healthcare and farming by rolling out several development pacts in central Uganda, similar to those tried by our colleagues in India.

We told communities to pick their own development agenda, then asked local politicians to commit to fulfilling that agenda. People were able to pick the issues that matter to them, and clearly described what they expect their leaders to deliver.

Some of the leaders refused, some signed up. Not surprisingly, more of the latter were re-elected than the former.

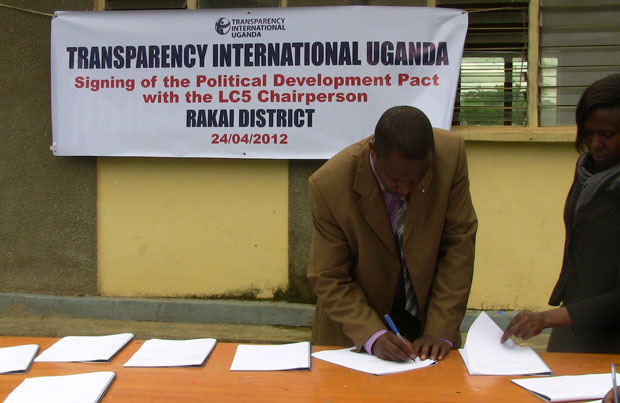

A regional politician signs a pact.

After the pacts were signed, citizens set up committees to monitor progress. Politicians and officials now often give the committees access to their offices to get information.

The result was relentless community pressure for better services. The committees personally counted drugs as they were being delivered. The list of drugs received is posted on notice boards. More staff have been hired, more mosquito nets delivered and more people are visiting the health centre. Parents have learnt to monitor budgets, and are now tracking school budgets too.

The people from my village are happy because they can receive all the basic drugs prescribed to them by the physician at no cost and drug shortages have become history in the health centre – A member of the Kyebe sub-county community

Another priority was government funding for subsistence farmers. The government provide funds to support farmers. Under the scheme, local authorities are supposed to use funds from the state to buy seeds and equipment for local subsistence farmers. The problem is they often buy sub-standard seeds and machinery and keep the difference.

We held review committees attended by both local politicians and government representatives. In the past, politicians had always blamed the other for failings. But when they were all in the same room, it suddenly became harder to duck responsibility.

Transparency International and community members witness the pact signing

We have managed to give farmers more control over the process. The criteria for selecting farmers who receive support was made simpler and more open. More farmers joined the government support programme, having been made aware of their rights and the selection process was made more open.

Our work continues.

In the north of the country, we are now helping citizens report problems in health care by sending SMS text messages. For example, they warned that malaria nets are not being distributed despite the fact that a health centre that recently received a delivery from central government. Read more on this here.

Connect with us on Facebook

Connect with us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter

Follow us on Twitter