Some time ago I argued on this blog that looking back into history provides a very promising source for inspiration and innovation in the fight against corruption. Many things we consider new to modern government, such as measures managing conflicts of interest and insulating decision-making from policy capture were foreshadowed by and startlingly resemble many measures introduced by Italian city states as early as the 13th century.

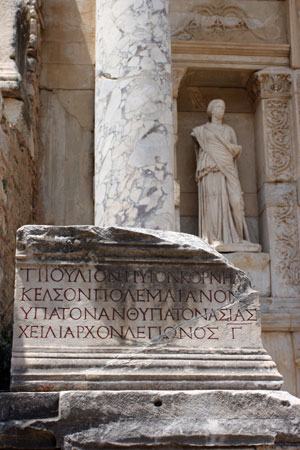

In Greek cities it was common practice to inscribe important public laws into stone columns.

More recently I stumbled upon the power and potential of history in relation to ambient accountability– how physical space and the built environment can be used to help people understand and assert their rights, fend off corruption and monitor what their governments do (read more in a recent working paper). I believe this concept provides a launch-pad for innovative initiatives. You could bring information about people’s rights more visibly into public space by painting it on walls or display public performance information onto buildings or screens posted outside important institutions.

Digging a bit deeper into the history of public projections and displays of rights, entitlements and public performance I learnt that this is something that can be traced back to really ancient times.

In Greek cities, for example, it was common practice to inscribe important public laws into stone columns and jot down more fleeting budgets onto wooden boards to be displayed prominently in public squares.

Ambient accountability in the 1860s.

It was not ever more powerful large urban LED screens and artistic laser projections of recent years that have lit up public space for the first time with illuminated information related to governments and governance, for example to mobilize people against health care fraud. “Magic lanterns” were already used for marketing in the 1860s, and also served to project quasi real-time election results onto buildings to inform large, attentively watching crowds.

None of these examples are particularly surprising when you consider that people without modern media and particularly without the Internet had to rely on other ways to achieve publicity for how the state works and how citizens could engage with it.

But working with spaces and places has rather been sidelined in times of online activism and social media galore. There is an urgent need to re-discover such strategies, not only to reach the disconnected, but also to ensure that activism does not exhaust itself online with cyberspace merely a virtual pressure valve to let off steam. Thinking ambient accountability and revisiting the many tactics to use space and place to communicate and mobilise through information is imperative to ensure that all this online creativity, commitment and engagement can find impactful outlets in the physical world. As the saying goes, history may not repeat itself, but it certainly rhymes. And it can give us much exciting food for thought to link the virtual and the physical much more systematically to empower people and help them fend off corruption.

Connect with us on Facebook

Connect with us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter

Follow us on Twitter