In Liberia, my country of birth, the word “corruption” has become a political dagger that we hurl at those with entrusted power. It is meant to shame, alienate, and render the “other” defenceless, thereby exonerating the thrower from any personal responsibility.

Yet, corruption is not a timeless tango between the public and private sectors alone. It is also the little acts of trickery that we engage in as a means of bypassing systems that we find cumbersome or problematic, no matter our station in life or where we live in the world. The only way to radically alter the discourse on corruption in Liberia, the UK and elsewhere is by involving children in a values revolution. Children are perfectly suited for this because it is in the earlier stages of development that we begin to form an ethical core.

In 2013, I wrote Gbagba, an anti-corruption school book for eight to 10-year-olds, to engage Liberian children in a national conversation about how individual integrity and collective accountability can facilitate post-conflict recovery. Gbagba – which loosely translated in the Bassa language means trickery – follows a few days in the life of Liberian twins, Sundaymah and Sundaygar, who leave their hometown of Buchanan to visit their aunt in Monrovia, Liberia’s capital. I wrote Gbagba to give young children the verbal tools to question the confusing ethical codes of the adults around them.

The space for political discourse around corruption in Liberia has widened because of an increasingly engaged citizenry and a relatively tolerant post-war regime, yet we need to move beyond the rhetoric. I knew that involving children in our national debate would stop the finger-pointing in its tracks, forcing us to think about solutions at the individual, local, and national levels. When children begin talking about how corruption affects their every-day lived realities, adults tend to listen. And they have in Liberia. Ever since I launched Gbagba, there has been a surge of public support for the book. For instance, Unesco devised a values education curriculum using the book as its core text, and the Ministry of Education placed the book on its list of supplemental texts for third to fifth graders. In 2015, I intend to embark on a national tour of the book, with possible pilots in other sub-Saharan African countries.

The space for political discourse around corruption in Liberia has widened because of an increasingly engaged citizenry and a relatively tolerant post-war regime, yet we need to move beyond the rhetoric. I knew that involving children in our national debate would stop the finger-pointing in its tracks, forcing us to think about solutions at the individual, local, and national levels. When children begin talking about how corruption affects their every-day lived realities, adults tend to listen. And they have in Liberia. Ever since I launched Gbagba, there has been a surge of public support for the book. For instance, Unesco devised a values education curriculum using the book as its core text, and the Ministry of Education placed the book on its list of supplemental texts for third to fifth graders. In 2015, I intend to embark on a national tour of the book, with possible pilots in other sub-Saharan African countries.

Some of my critics have argued that involving children in the fight against corruption is misguided because they can’t change policy. But Liberia’s problem is practice, not policy. If one took a cursory glance at our perfectly pitched post-war policies and programs to address public sector corruption, one would assume that the country was doing rather well. After all, institutions such as the General Auditing Commission, the Governance Commission, the Anti-Corruption Commission, and the Public Procurement and Concessions Commission were all created to stamp out graft. Yet, they are toothless and prone to political manipulation. Furthermore, these bodies do not address the corruption that is enmeshed in every day human interaction. Contrary to normative claims made by development actors, I believe strongly that institutions are not the panacea to mitigating corruption. People are. And the younger, the better.

To date, I have come across no anti-corruption strategies that employ children as conduits of change. Perhaps we all need to step out on a limb and try something new.

(This blog was originally posted on the Transparency International UK website, you can see the original here.)

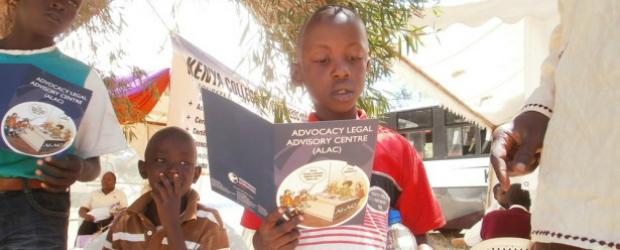

Carousel image: Copyright, Transparency International Kenya

Connect with us on Facebook

Connect with us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter

Follow us on Twitter