Let the buyer beware: cheap clothing sometimes comes at a high price. Since the fire that killed 112 clothing workers in a Bangladesh factory last month, the big global retailers supplied by the factory are being asked what they do to make sure the products we buy come from safe factories?

How much is corruption a factor ?

At Transparency International, we often say “corruption kills”, especially if governments fail to enforce safety standards.

Corruption by collusion or omission, and injustice by weak law enforcement, are big problems in most of the countries that make the clothes you wear.

In many factory fires, reports and allegations later emerged that corruption allowed the factory to stay in business without having proper fire exits or respect for safety standards.

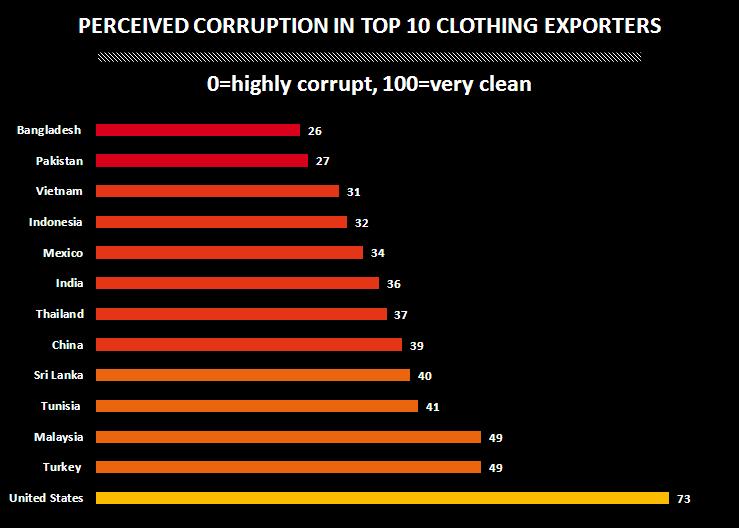

This is not Bangladesh’s first deadly fire this year, nor is the problem is confined to Bangladesh. Similar tragedies have occurred in other countries where the perception is that corruption is a high risk: China, Vietnam, Mexico, India and Pakistan – all countries with corruption problems according to the Corruption Perceptions Index 2012 (see table above).

A risk of public sector corruption opens the door to several corrupt ways to keep an unsafe factory operating:

Bribery or collusion

In a tragic, and all too common, example of negligent approach to safety inspection, the factory in Dhaka had been cleared by safety checks a month before the tragedy. Corruption may be one of the reasons why regulations are flouted – and facilities get their seal of approval to keep operating. Sometimes, bribery does not take place but weak enforcement of safety standards by public officials leaves workers exposed.

Factory owners can bribe officials to avoid or by-pass safety checks. Officials and factory owners have too cosy a relationship. A Human Rights Watch report on Dhaka’s tanneries warned

inspectors prioritize good relations with managers and give them advance notice before an inspection.”

adding that the Ministry of Labour’s Inspection Department has just 18 inspectors to monitor an estimated 100,000 factories in Dhaka.

Undue influence on policy:

Why don’t governments put more resources behind worker safety and implementing policies to protect them? According to the New York Times, in the Bangladesh parliament

roughly two-thirds of the members belong to the country’s three biggest business associations. At least 30 factory owners or their family members hold seats in Parliament, about 10 percent of the total.”

Lack of protection for whistleblowers

What happens when workers speak up about unsafe conditions? In the case of Bangladeshi trade unionist Aminul Islam, harassment, torture and murder, with rights groups saying he had been harassed for some time. Cases like this discourage others from reporting problems, and it is up to governments to make sure whistleblowers are protected from reprisals.

Lack of access to information

How about the multinationals supplied by the factories in these countries? Our reports have called on them to be more open about their subsidiaries and anti-corruption programmes.

For example, the Clean Cloths Campaign are criticising investigators of a factory fire in Pakistan for not sharing information about who buys clothes from the factory with the victims or workers’ groups.

A boy soaks hides in a pit of diluted chemicals in a Dhaka tannery. Click on the image to see other photographs of Dhaka’s tanneries. © 2012 Arantxa Cedillo for Human Rights Watch

Global clothing brands should realise the true message of Corruption Perceptions Index.

The burden lies in the failure of the governments to challenge impunity and upon businessmen who are in a desperate game of making quick money by colluding with powers that be, in a context where business is increasingly synonymous with politics.

Nevertheless, do you think it is enough for buyers of garments from these countries like Walmart to cancel their order after such deadly accidents have taken place?

Should other suppliers of your clothes follow such example of chopping off the head for the headache and thereby punish the garments workers, 90 per cent of whom are women, for the corrupt activity and impunity of the high and mighty?

The Corruption Perceptions Index is not intended to scare business and investment away from countries with a low rank, its lets them know the context in which they will operate. It should remind them of the importance of conducting business with a sense of responsibility and integrity.

When you are confronted with the news of such tragic loss of lives for corruption don’t you consider it your responsibility to ask whether importers of those products could also do more to ensure stricter compliance to safety standards rather than rapidly dumping business partners when tragedies occur but playing safe by omission the rest of the time?

Have you looked at your clothes and checked out where they are made? Perhaps Bangladesh or Sri Lanka or Honduras?

Now look at where they score on the Corruption Perceptions Index, and tell us your reaction in the comment area below.

Carrousel image: Flickr / Creative commons: Dave Wilson Cumbria

Connect with us on Facebook

Connect with us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter

Follow us on Twitter